Like many women, C.D., a woman in her early twenties, never expected to be forced into prostitution to fuel her addiction to heroin. Nor did, A.Z., T.B., A.O., N.S., C.G., or J.A., the other known trafficking victims of Barry Davis. Davis exploited them when they were most vulnerable, leading them into a world of violence and sex against their will.

A Taste for Vulnerable Women Addicted to Heroin

C.D. began a driver’s education course in Boston, Massachusetts, in April 2015. She met Barry Davis during one of these classes. Davis was a seemingly kind man in his mid-30’s who grew up in a nearby town called Burlington. Davis quickly noticed that C.D.. was a heroin user because of the track marks running down her arms.1 Unbeknownst to C.D., she was the next heroin addict Davis planned to exploit.

Davis befriended C.D., offering her heroin during a lunch break so she would not get sick from withdrawal. They exchanged numbers and started talking outside of class. When Davis called C.D. a few days later, he invited her to go to New Jersey with him. He offered to take care of her and give her a steady supply of heroin to satiate her cravings.

A few days later, C.D. and two other young women joined Davis on a trip to New Jersey.2 The friendship quickly turned violent. Davis hit C.D. and swore it would not be the last time unless she followed his rules. His violence struck fear into all three women. Exploiting C.D.’s addiction, Davis promised her heroin in exchange for the profits from commercial sex acts Davis intended C.D. and the other women to perform in New Jersey. He threatened to cut her off unless she prostituted for him. The threats of withdrawal and further violence were enough to force C.D. into compliance.3

A few days later, C.D. and two other young women joined Davis on a trip to New Jersey.2 The friendship quickly turned violent. Davis hit C.D. and swore it would not be the last time unless she followed his rules. His violence struck fear into all three women. Exploiting C.D.’s addiction, Davis promised her heroin in exchange for the profits from commercial sex acts Davis intended C.D. and the other women to perform in New Jersey. He threatened to cut her off unless she prostituted for him. The threats of withdrawal and further violence were enough to force C.D. into compliance.3

When they arrived in New Jersey, Davis rented a hotel room and posted an advertisement for C.D. on Backpage.com, a classified services website well-known for prostitution.4 In response to the Backpage.com advertisement, a man came to the hotel room and paid for sex with C.D. Davis pocketed the money, and C.D. got heroin.5

That night, C.D. contacted her sister and mother when no one was watching and told them she wanted to come home. The police arrived at the hotel and found C.D. and the two other young women, but Davis had already slipped away.6

After evading arrest, Davis continued to run his prostitution ring through other women he had previously exploited. For example, Davis was able to get to his next victim, T.B., through her relationship with a young woman he had recruited before, A.Z. T.B. met A.Z. at a heroin detoxification center in Tewksbury, Massachusetts in August 2015. Close in age and similarly struggling through their heroin addictions, T.B. and A.Z. became fast friends. When the two decided to leave the detoxification center, A.Z. called Davis to pick them up. T.B. trusted this friend of a friend. Davis took them to an apartment in Massachusetts and gave them heroin and cocaine.7

Just as he did with C.D. a few months earlier, Davis drove the two to a hotel, this time in Connecticut, and posted advertisements for their sexual services on Backpage.com. He used violence — hitting A.Z. in front of T.B. and threatening to do the same to T.B. — to force the women to prostitute for him. Furthermore, as with C.D., Davis controlled the women’s access to heroin, withholding the substance until the women handed over the cash from their sexual exchanges. After the women provided sex to their Backpage.com customers, Davis again took the cash and provided the women with heroin.8

Fortunately, after a couple of days, T.B. found the phone Davis took from her and frantically texted a friend that she was being held against her will and prostituted. On August 26, 2015, the police arrived at the hotel — this time, before Davis could evade arrest.9

Sentencing & Appeal: Did the Government Breach the Plea Agreement?

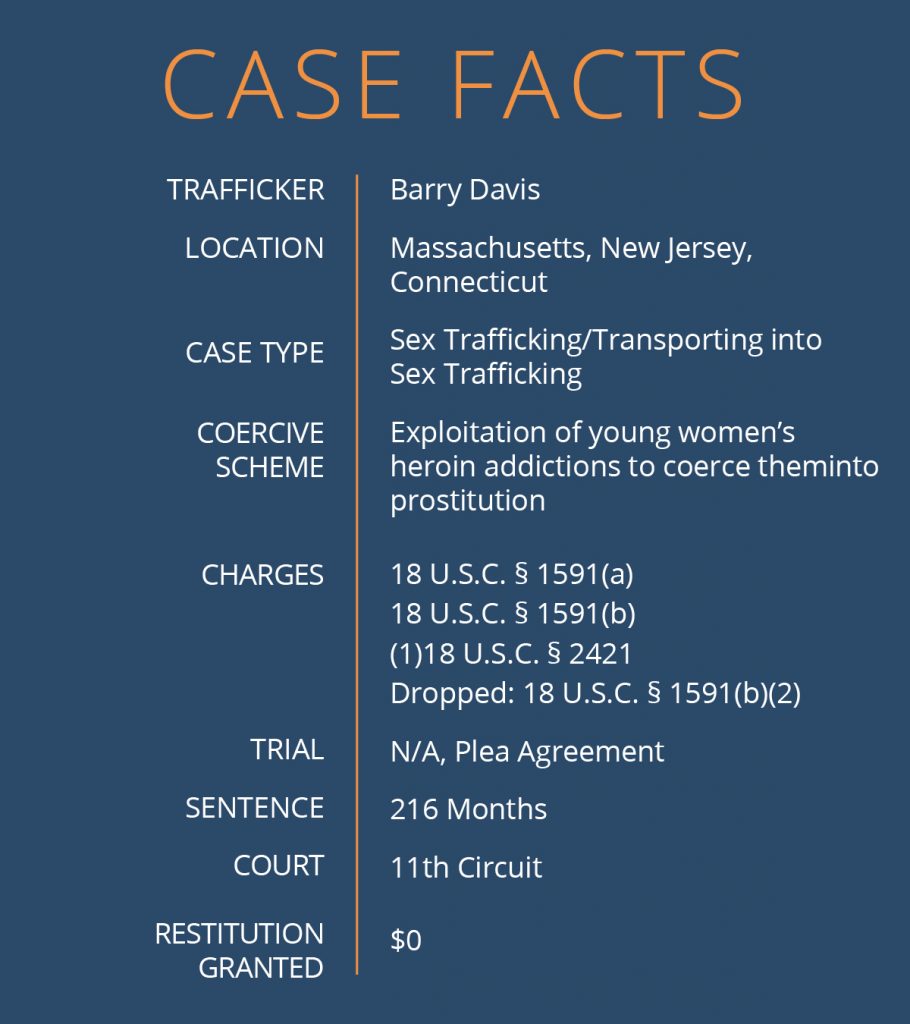

On March 27, 2017, just before his case went to trial, Davis entered into a plea agreement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts. Davis pled guilty to charges of sex trafficking by force, fraud, or coercion, and transporting persons into prostitution under sections 1591 and 2421 of Title 18 of the U.S. Code in relation to his exploitation of C.D., A.Z., and T.B. in 2015. A federal judge in Massachusetts sentenced Davis to 216 months in prison, well within the 180-240 month sentencing range set by the plea agreement. As part of the plea agreement, the government agreed to dismiss charges against Davis for his coercive sex trafficking of A.O. and minor N.S.10

Image of Barry Davis. Source: https://www.fox61.com/article/news/local/outreach/awareness-months/milford-police-track-cell-phone-arrest-man-accused-of-human-trafficking-prostitution/520-3719da21-98a3-48ff-9ea9-0f8c8a001bdb.

During sentencing, the Sentencing Court allowed victim impact statements from four victims Davis exploited. One victim testified that Davis used his autistic son to book hotels to deflect suspicion. Another described Davis’ persistent use of violence and abuse as a means of coercion, including how he hunted down his victims after they escaped. One victim could not testify at all because prior to the sentencing hearing, she died of a drug overdose.

Very little of this information, Davis argued, should have been allowed before the sentencing court.11

Davis appealed his 216-month sentence to the First Circuit Court of Appeals in November 2017.12 He alleged, among other things, that the government breached his plea agreement by introducing statements from C.G. and A.O. at his sentencing hearing. Since the charges involving these victims were dismissed from — or never included in — the charges against him, the government, Davis argued, should not have provided information about them at all during sentencing. Davis objected to C.G. and A.O.’s testimonies at the sentencing hearing, but the court allowed them, assuring Davis that the statements would not affect the guideline calculations. He also argued that the government should not have included information about these victims in the Statement of Offense Conduct it sent to the U.S. Probation Office.13

The First Circuit reviewed Davis’s sentence for “plain error,” which means the Court considered whether there was a clear and obvious error that hurt the complainant’s rights and impaired the fairness of the judicial proceedings. The First Circuit affirmed the lower court’s decision, finding that the government did not in fact breach the plea agreement. Heavily citing previous First Circuit cases on issues of plea agreement interpretation, the First Circuit found that Davis’ plea agreement did not specifically limit the evidence the government could convey to the court regarding the scope of the defendant’s exploitative conduct. The Court also pointed to language in the plea agreement which explicitly stated “[n]othing in this Plea Agreement affects the U.S. Attorney’s obligation to provide the Court and the U.S. Probation Office with accurate and complete information regarding this case.”14 Lastly, the First Circuit found that because the 216-month sentence fell within the 180-240 month sentence guideline proposed in the plea agreement, the government’s actions did not deny Davis the benefit of the plea agreement.15

Dropped Charges Do Not Silence Victims’ Voices

Although Davis’ argument the government breached a plea agreement is not unique, this argument typically comes in the form of defendants alleging that the government requested — and was granted — a higher sentence than proposed in the agreement. This is the first time a federal appellate court, in the trafficking in persons context, has addressed whether a plea agreement is violated when a sentencing court admits statements from victims who were not specifically named in the charges to which the defendant pled guilty.

In this case, the First Circuit highlighted the importance of the government presenting all evidence related to a case to the court during sentencing. This means — at least in the First Circuit — a sentencing court is permitted to admit victim statements regarding the defendant’s exploitative conduct, even by victims not named in a charge to which the defendant pleads guilty, unless otherwise stipulated by the plea agreement. By nature of a plea agreement, the crimes committed against some victims may be dismissed. Accordingly, the First Circuit allows for victims of human trafficking to be heard when their perpetrator is being sentenced, even when they are not named in the charge of conviction.

Through this decision, the First Circuit makes clear: information that helps the court assess a defendant’s background, character, and conduct can be heard by Probation and the Sentencing Court, so long as the court delivers a sentence within the guidelines of the plea agreement. Courts should therefore consider all evidence relevant to the defendant’s conviction in sentencing, including evidence from victims not named in the charging instruments. The First Circuit’s decision underscores the value of victim statements in a court’s determination of an appropriate sentence. Used judiciously, this decision may have a profound effect on the ability of victims to have their day in court.

- 1 U.S. Attorney’s Office District of Massachusetts, Burlington Man Sentenced for Sex Trafficking, United States Dept. of Justice (Oct. 20, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ma/pr/burlington-man-sentenced-sex-trafficking

- 2 Brief for the United States, United States v. Davis, 923 F.3d 228 (2018) (No. 17-2100)

- 3 Id.

- 4 In April 2018, the federal government seized and shutdown Backpage.com. Criminal and civil law suits are currently pending against Backpage.com for its facilitation of and financial benefitting from commercial sex.

- 5 Brief for the United States, United States v. Davis (2018)

- 6 Id.

- 7 Id.

- 8 Id.

- 9 Id.

- 10 Id.

- 11 Id.

- 12 “Burlington Man Who used Drugs, Beatings To Force Women Into Prostitution Gets 18-Year Sentence,” Patch (Oct. 20, 2017), https://patch.com/massachusetts/burlington/burlington-man-who-used-drugs-beatings-force-women-prostitution-gets-18

- 13 United States v. Davis, 923 F.3d 228 (1st Cir. 2019)

- 14 Id.

- 15 Id.

- 16 Id.