By: ZACH BUCHANAN

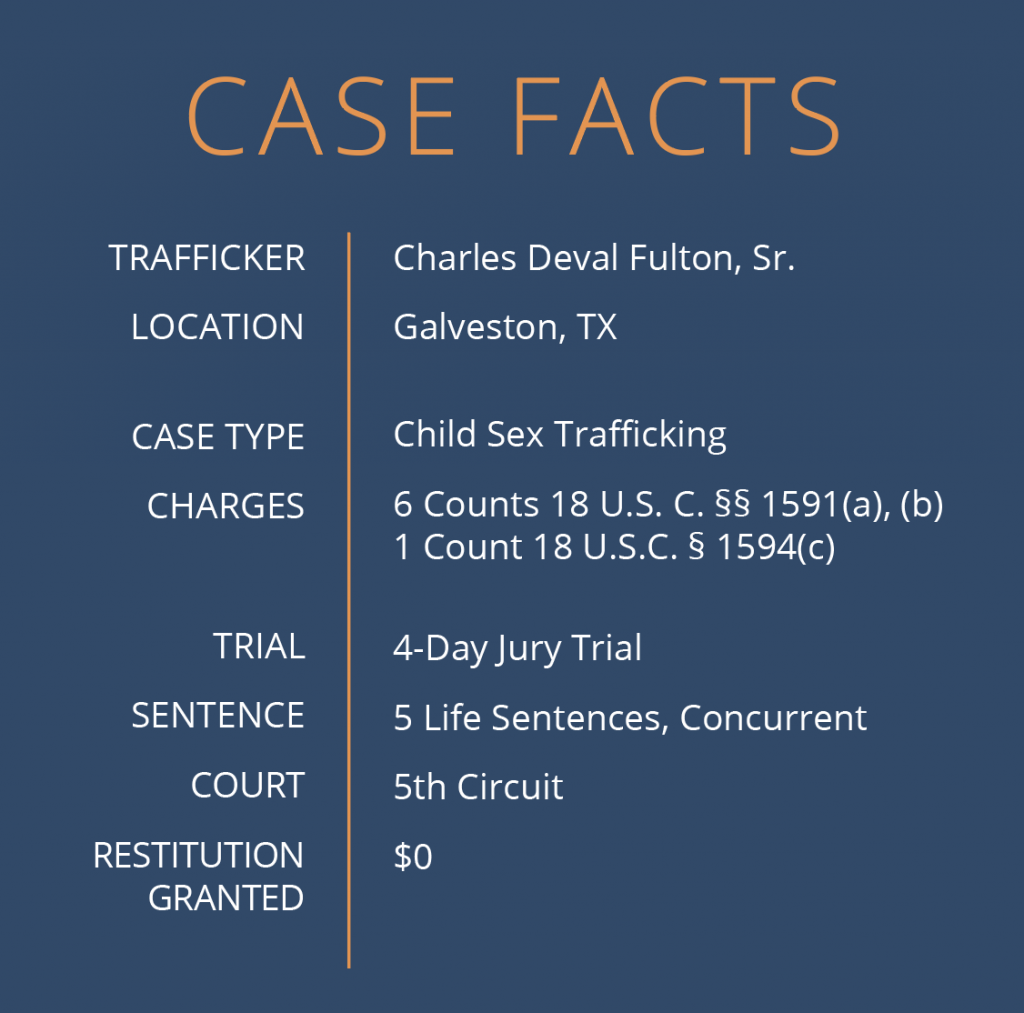

In 2015, Charles Devan Fulton, Sr. (aka “Black” and “Blacc”) forced girls as young as 15 to engage in commercial sex acts for his profit. If they refused, he “beat [them],”1 hit them,2 and even choked one young girl,3 all as part of his trafficking scheme. Even though a jury found Fulton guilty of four counts of sex trafficking, he almost walked free due to an error in the wording of his criminal indictment.

Connecting the Dots That Led to Fulton

Fulton met Minor Victim 1 (MV1) in February 2014. Originally, the two were acquaintances. Four months later, when MV1 was only 15 years old, Fulton began prostituting her out of his home. He ran ads to solicit buyers on Backpage.com — an online advertising service where traffickers often post ads of their victims4 — and forced her to turn over all her earnings from her forced sexual acts. He knew her age but disregarded it entirely.

The next year, in February 2015, the District Attorney’s office in Galveston, Texas, began investigating Fulton on suspicion of human trafficking. The District Attorney then contacted FBI Special Agent (SA) Rennison to begin interviewing potential victims. When SA Rennison interviewed MV1, she told him the names of several girls and women Fulton knew — some of whom he prostituted — including a second minor victim (MV2) and M.J.C. When SA Rennison interviewed M.J.C., she provided him with the names of six additional juvenile females Fulton trafficked for prostitution.

Fulton did not work alone. His co-conspirators, Dominique Warner, Lawrence James Julian, and Charmaine Potts, helped Fulton by paying for hotel rooms, driving the girls to and from the hotels, and posting ads of the girls on Backpage. The co-conspirators received money for their help — approximately 40 percent of proceeds from the trafficking. Fulton pocketed the remaining 60 percent.

Fulton did not work alone. His co-conspirators, Dominique Warner, Lawrence James Julian, and Charmaine Potts, helped Fulton by paying for hotel rooms, driving the girls to and from the hotels, and posting ads of the girls on Backpage. The co-conspirators received money for their help — approximately 40 percent of proceeds from the trafficking. Fulton pocketed the remaining 60 percent.

After SA Rennison finished his interviews, the Galveston Police Department (GPD) pulled files on the six juveniles M.J.C. identified. All six girls were linked to Fulton through offense and incident reports. GPD listed some of the girls as runaways whom officers had previously found at Fulton’s house. SA Rennison also conducted a search of Backpage and found ads for MV1 and another girl M.J.C. identified. Other identified victims confirmed Fulton and his co-conspirators drove them to “dates,” took the girls’ money, and brought food to them to support the trafficking enterprise.

GPD then obtained a search warrant for Fulton’s house, while investigating his narcotics activities. During that investigation, the FBI searched Fulton’s cell phone and found files linking him to five of the minor victims and exhibiting signs of sex trafficking.

In May 2015, a grand jury indicted Fulton on two counts of sex trafficking and one count of conspiracy to commit sex trafficking in the Southern District of Texas. A year later, in May 2016, the government filed a superseding indictment, adding four counts of sex trafficking (with a different minor victim in each count) and one count of conspiracy.5 A jury found Fulton guilty of four of the six total sex trafficking counts as well as the conspiracy count. The district court sentenced him to concurrent life terms.

Fulton appealed his conviction to the Fifth Circuit on several grounds. On one issue, Fulton argued the district court violated the Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Amendment by constructively amending the indictment — that is, Fulton claimed he was convicted under a theory of the crime he was not charged within the initial indictment.

Improper Amendment of the Indictment

Under the federal human trafficking statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1591, the U.S. Government can charge sex trafficking of minors under a variety of theories — sets of facts that, when put together, satisfy the different elements of the sex trafficking offense. The Government could have charged Fulton under a theory that he “had a reasonable opportunity to observe” the victim was a minor.6 Courts are still debating the definition of a “reasonable opportunity to observe”,7 but this is the most lenient of the charging theories. The other theories require proving Fulton “knew, or recklessly disregarded the fact”8 that the victim was a minor.9

The indictment in Fulton’s case asserted Fulton “knew or recklessly disregarded” his victims were under the age of 18 — it did not charge Fulton with a “reasonable opportunity to observe” the victims’ age. However, the district court told the jury the Government did not have to prove Fulton’s actual knowledge of the victims’ minor status if they proved he had a reasonable opportunity to observe the victims. Fulton argued on appeal that the district court, by giving this instruction, imported the concept of reasonable opportunity to observe into the case and allowed the jury to convict him “on a basis broader than what was stated by the indictment.”10

In consideration of this claim, the Fifth Circuit looked to one of its prior cases, United States v. Lockhart, 844 F.3d 501 (5th Cir. 2016). In that case, the Circuit “discussed the exact issue presented by Fulton.”11 One of the Lockhart defendants was convicted of sex trafficking of children and conspiracy, but the language of the indictment alleged he “kn[ew] and . . . reckless[ly] disregard[ed]”12 that the victim was a minor, even though the jury instruction included the “reasonable opportunity to observe” language. The Fifth Circuit held that when a district court gave a jury instruction using § 1591(c) language and that language was not in the indictment, “the district court materially modified an essential element of the indictment by transforming the offense from one requiring a specific mens rea [the state of mind necessary to be held responsible for a crime] into a strict liability offense [an offense where state of mind does not matter].”13

In Lockhart, the Fifth Circuit reversed the conviction for one of two defendants whose indictments had been constructively amended — the defendant who made a timely objection to the jury instruction. For the defendant who did not object, the Circuit reviewed his conviction for plain error — they looked to see if the mistake of amending the indictment was patently obvious and warranted reversal. When reviewing for plain error, the Fifth Circuit “decline[d] to exercise [its] discretion to reverse because of the ‘substantial evidence against’ the defendant.”14 Because, in this case, Fulton did not object either, they also reviewed Fulton’s conviction for plain error. The Circuit held that the evidence against Fulton was also “substantial,” and so they would not vacate his convictions based on the jury instruction, even though the “reasonable opportunity” language was not in the indictment.

Looking Forward from Fulton

Based on the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, the court may well have overturned Fulton’s conviction if he had made a timely objection to the jury instruction below. For prosecutors in the Fifth Circuit and circuits where the issue is undecided15, Fulton serves as a warning: in order to convict a defendant under the more lenient “reasonable opportunity to observe” standard of § 1591(c), the Government must include that language in the indictment. When that language is missing, convictions based on such a jury instruction may be overturned on appeal.

- 1 United States v. Fulton, 928 F.3d 429, 438 (5th Cir. 2019)

- 2 Id.

- 3 Id.

- 4 Backpage.com has since been seized by the U.S. Department of Justice. For other stories on Backpage, see https://staging.traffickingmatters.com/page/2/?s=backpage.

- 5 Three co-conspirators were also charged with conspiracy and with sex trafficking.

- 6 18 U.S.C. § 1591(c).

- 7 For more discussion of how courts are understanding what suffices as a “reasonable opportunity to observe,” see Katherine Carey, Watch Your Language: How Charging Language, or the Lack Thereof, Can Have Unintended Consequences, Trafficking Matters, https://staging.traffickingmatters.com/watch-your-language-how-charging-language-or-the-lack-thereof-can-have-unintended-consequences/.

- 8 18 U.S.C. § 1591(c).

- 9 The Fifth Circuit has ruled that a “reasonable opportunity to observe” the victim is a minor is sufficient for a conviction. See United States v. Copeland, 820 F.3d 809, 813 (2016) (“. . . today, we . . . join[ ] the Second Circuit in concluding that . . . the Government ‘need not prove any mens read with regard to the defendant’s awareness of the victim’s age if the defendant had a reasonable opportunity to observe the victim.’”) (quoting United States v. Robinson, 702 F.3d 22, 34 (2d Cir. 2012)).

- 10 Fulton, 928 F.3d at 438.

- 11 Id. at 439.

- 12 Lockhart, 844 F.3d at 515.

- 13 Id. at 515–16.

- 14 Fulton, 928 F.3d at 429 (quoting Lockhart, 844 F.3d at 515 n.3).

- 15 Some Circuits, like the Sixth Circuit, have not decided whether the “reasonable opportunity to observe” provision is a distinct legal theory. See, e.g., United States v. Davis, 711 F. App’x 254, 258 fn.2 (6th Cir. 2017). Other Circuits, like the Ninth, have decided that “if the government proves the ‘reasonable opportunity to observe’ prong, it is relieved from proving the defendant’s knowledge or recklessness regarding the victim’s minority.” United States v. Davis, 854 F.3d 601, 604 fn.2 (9th Cir. 2017).