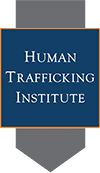

By: SARAH HAMILL

Angela McCullough, a 40-year-old African American mother of four, left her class at Faulkner University before dark. A police officer pulled her over for failure to turn on her headlights and having a cracked taillight. The officer not only gave her a ticket but also subsequently arrested her for warrants on unpaid fines. The officer brought her to the Montgomery County Jail, where she was detained because she could not afford bail. Judge Hayes sentenced her to 85 days in jail until she paid off her fine through jail time. Ms. McCullough was eventually released after 19 days because she used money intended for her education to pay off the fines. Because of this arrest, she lost her job and was unable to continue her classes at Faulkner University.

Four years prior to this arrest, Ms. McCullough was arrested for failure to pay fines from traffic tickets and was jailed for 66 days until she worked off her fines. Each time Ms. McCullough was in jail,  she was forced to perform labor to lower her sentence and pay off her traffic fines sooner. Ms. McCullough’s jail labor included supervising a female inmate suffering from Hepatitis C who was on suicide watch. Ms. McCullough stood watch for two hours, during which time the inmate slit her wrist and the jail required Ms. McCullough to clean up the blood. Ms. McCullough’s jail labor also included cleaning up feces in jail cells.

she was forced to perform labor to lower her sentence and pay off her traffic fines sooner. Ms. McCullough’s jail labor included supervising a female inmate suffering from Hepatitis C who was on suicide watch. Ms. McCullough stood watch for two hours, during which time the inmate slit her wrist and the jail required Ms. McCullough to clean up the blood. Ms. McCullough’s jail labor also included cleaning up feces in jail cells.

The City’s Scheme: Jail Low-income Offenders to Raise Revenue

Ms. McCullough is not alone in her story. Nine other African American plaintiffs along with a class of similarly situated persons have been subjugated to these practices in the City of Montgomery. These plaintiffs filed suit against the City, former presiding Judge Hayes, current presiding Judge Westry, two chiefs of police, and the mayor for their alleged involvement in a scheme to target low-income, minority neighborhoods to increase municipal revenue through traffic fines.

The complaint alleged that officers made routine stops in low-income communities, especially after church services in minority neighborhoods, and gave out traffic fines. During these stops, the officers determined if the person stopped had previous unpaid fines. Those unable to pay the fines were incarcerated. Each day in jail equaled $50 towards the fine. If the inmates worked while in jail, they could earn an extra $25 per day toward their payments and be released sooner. However, the jail’s system of tracking the days inmates worked was inaccurate and some days were not counted, increasing the amount of time the inmates remained incarcerated.

The city gave those incarcerated a choice: work for the City while in jail, shortening your total time, or refuse to work for the City and spend more time in jail. The City incarcerated the plaintiffs for unpaid traffic fines without considering whether the plaintiffs could afford the fines and without considering alternatives to incarceration, such as community service.

Appealing to the 11th Circuit: Defendants’ Seek Dismissal of Claims

The defendants filed a motion to dismiss the case claiming the plaintiffs failed to state a claim for which relief could be granted. The District Court for the Middle District of Alabama dismissed some claims but refused to dismiss the claim of forced labor in jail. The City, two judges, the mayor, and two chiefs of police appealed, attempting to dismiss all of the claims. The 11th Circuit dismissed the City’s appeal but heard the individuals’ appeals.

Judicial Immunity: Protection for Judges

The two judges—former presiding Judge Hayes and current presiding Judge Westry—appealed, claiming judicial immunity from suit. According to the United States Supreme Court, “A judge enjoys absolute immunity from suit for judicial acts performed within the jurisdiction of his court.”1 In deciding whether a judge is entitled to absolute immunity, courts look to see whether the judge’s actions were within his judicial capacity. Whether the act was appropriate or suitable for the situation is not a consideration, but only whether the act was a judicial act.2 Furthermore, a judge is entitled to judicial immunity regardless of whether the act was a mistake, purposeful and malicious, or outside the scope of his authority.3 In fact, “the ‘tragic consequences’ that result from a judge’s acts do not warrant denying him absolute immunity from suit.”4

The 11th Circuit follows a four-factor test to determine if a judge’s actions were taken in his judicial capacity: whether “(1) the precise act complained of is a normal judicial function; (2) the events involved occurred in the judge’s chambers; (3) the controversy centered around a case then pending before the judge; and (4) the confrontation arose directly and immediately out of a visit to the judge in his official capacity.”5

The 11th Circuit found every allegation against the judges was acting within the judges’ judicial capacities. This list of allegations included failing to adequately advise plaintiffs of their rights, ordering civil incarceration until fines were paid, and providing opportunities for plaintiffs to work to decrease their sentences. Therefore, the judges were entitled to judicial immunity from the suit.

State-Agent Immunity: Protection for City Officials

Mayor Strange, former chief of police, Chief Murphy, and current chief of police, Chief Finley, also appealed, claiming state-agent immunity. The 11th Circuit and the Supreme Court have noted, “[state-agent] immunity shields government officials acting within their discretionary authority from liability unless the officials ‘violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.’”6 This means a state-agent, like the chief of police or the mayor, cannot be sued for just any act—the act must have malicious, fraudulent, in bad faith, under a mistaken interpretation of the law, or outside their discretionary authority.7 In this case, the plaintiffs acknowledged that all the acts alleged in the complaint were within the mayor and chiefs’ discretionary authority. Therefore, in order for the plaintiffs to overcome this immunity, they needed to provide sufficiently detailed allegations in their complaint, statements that are not merely conclusory or speculative, showing the officials acted maliciously, fraudulently, in bad faith, or under a mistaken interpretation of the law.8

Mayor Strange, former chief of police, Chief Murphy, and current chief of police, Chief Finley, also appealed, claiming state-agent immunity. The 11th Circuit and the Supreme Court have noted, “[state-agent] immunity shields government officials acting within their discretionary authority from liability unless the officials ‘violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.’”6 This means a state-agent, like the chief of police or the mayor, cannot be sued for just any act—the act must have malicious, fraudulent, in bad faith, under a mistaken interpretation of the law, or outside their discretionary authority.7 In this case, the plaintiffs acknowledged that all the acts alleged in the complaint were within the mayor and chiefs’ discretionary authority. Therefore, in order for the plaintiffs to overcome this immunity, they needed to provide sufficiently detailed allegations in their complaint, statements that are not merely conclusory or speculative, showing the officials acted maliciously, fraudulently, in bad faith, or under a mistaken interpretation of the law.8

The 11th Circuit held that the plaintiffs did not overcome the application of state-agent immunity because, in the complaint, the plaintiffs merely stated conclusions like “the mayor and chiefs of police adopted and administered an unlawful scheme to increase municipal revenue.” The court highlighted that these claims were conclusory and without sufficient factual details connecting the mayor and the chiefs to the alleged acts. The 11th Circuit furthered emphasized that the complaint did not provide any facts regarding the mayor or police chiefs’ management policies or knowledge of the alleged scheme. There were no facts to show any of those individuals were present when the judge sentenced the plaintiffs or when the jail forced the plaintiffs to work. Therefore, the 11th Circuit dismissed the case against Mayor Strange, Chief Murphy, and Chief Finley.

Judicial and state agent immunity are concepts implemented by all states and are not likely to change, especially in Alabama since the Alabama Constitution directly grants this immunity. But that does not mean government actors can never be held accountable. While judicial immunity makes it difficult to hold judges accountable for decisions within their courtrooms, if judges act outside of their judicial capacity, they will be held accountable for those actions. Furthermore, if a state-agent has truly participated in or benefitted from a forced labor scheme, the plaintiffs’ complaint must provide sufficiently detailed factual allegations in order to overcome this immunity. The details in the complaint are the key to proving that immunity should not apply given the nature of the agent’s acts. Thus, a trafficking victim’s ability to recover in a civil suit of this nature depends on a carefully crafted complaint.

- 1 Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349, 356–57 (1978) (emphasis added); see also Dykes v. Hosemann, 776 F.2d 942, 945 (11th Cir. 1985) (en banc).

- 2 See Mireles v. Waco, 502 U.S. 9, 13 (1991); see also Sibley v. Lando, 437 F.3d 1067, 1071 (11th Cir. 2005) (stating that the court does not ask if civil incarceration is appropriate for the case, but whether the judge was acting in his judicial capacity in ordering civil incarceration).

- 3 See Dykes, supra note 1, at 947.

- 4 McCullough v. Finley, 907 F.3d 1324, 1331 (11th Cir. 2018) (quoting Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. at 363).

- 5 Dykes, supra note 1, at 946.

- 6 Franklin v. Curry, 738 F.3d 1246, 1249 (11th Cir. 2013) (quoting Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800, 818 (1982)).

- 7 “Under Alabama law, state-agent immunity shields government officials acting within their discretionary authority from liability unless the officials ‘acted willfully, maliciously, fraudulently, in bad faith, beyond his or her authority, or under a mistaken interpretation of the law.’” McCullough, 907 F.3d at 1333 (quoting Hill v. Cundiff, 797 F.3d 948, 980–81 (11th Cir. 2015)).

- 8 See Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009) (In order to assert a plausible claim, the factual allegations must “allow[ ] the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged”).