By: ASHLEIGH PELTO

On April 15, 2017, hotel staff at the Quality Inn in Fargo, North Dakota called 911. Anthony Donte Collier had just beaten a woman and urinated on her. The hotel staff made the call while hiding the woman in the hotel’s laundry room for protection.

Over the following months, law enforcement discovered evidence Collier was not only abusing this woman but likely abusing and trafficking several other women for sex as well. During their investigation, law enforcement officers uncovered a Facebook group (“Pimps n Hos”) which Collier created to actively recruit women to serve as prostitutes. After recruiting women on Facebook, Collier then took provocative photos of the women and posted them on Backpage.com1 to solicit purchasers for sexual services.

Over the following months, law enforcement discovered evidence Collier was not only abusing this woman but likely abusing and trafficking several other women for sex as well. During their investigation, law enforcement officers uncovered a Facebook group (“Pimps n Hos”) which Collier created to actively recruit women to serve as prostitutes. After recruiting women on Facebook, Collier then took provocative photos of the women and posted them on Backpage.com1 to solicit purchasers for sexual services.

In November 2017, while surveilling Collier, police saw him make frequent visits to the same Quality Inn where he was first arrested. This time, he brought a different woman who police recognized from Collier’s Facebook page. In fact, Collier posted a picture of himself holding the end of a leash wrapped around this woman’s neck.

Collier’s Deceitful Tactics

Collier used many different methods to recruit women for his trafficking enterprise. In addition to social media recruitment, Collier also lured women into his trafficking scheme under the false pretense of an offer to work as a receptionist at his company (BGI Promotions). According to Collier, the company existed to promote up-and-coming rap artists. Other times, Collier feigned romantic relationships to build a false sense of trust and security with the women he would later exploit. He recruited one of his victims from a job at Walmart, another from work as a waitress, and another from a drop-in center for homeless and disadvantaged youth. Once the women believed they were working for Collier’s company, he executed the “bait-and-switch,” employing verbal threats and physical violence to keep the women compliant. For example, he told one woman if she ever withheld money from him it would be “the last thing [she was] going to do.” He even knocked a woman unconscious for trying to leave his house to see her children.

Charges, Convictions, and Collier’s Challenges

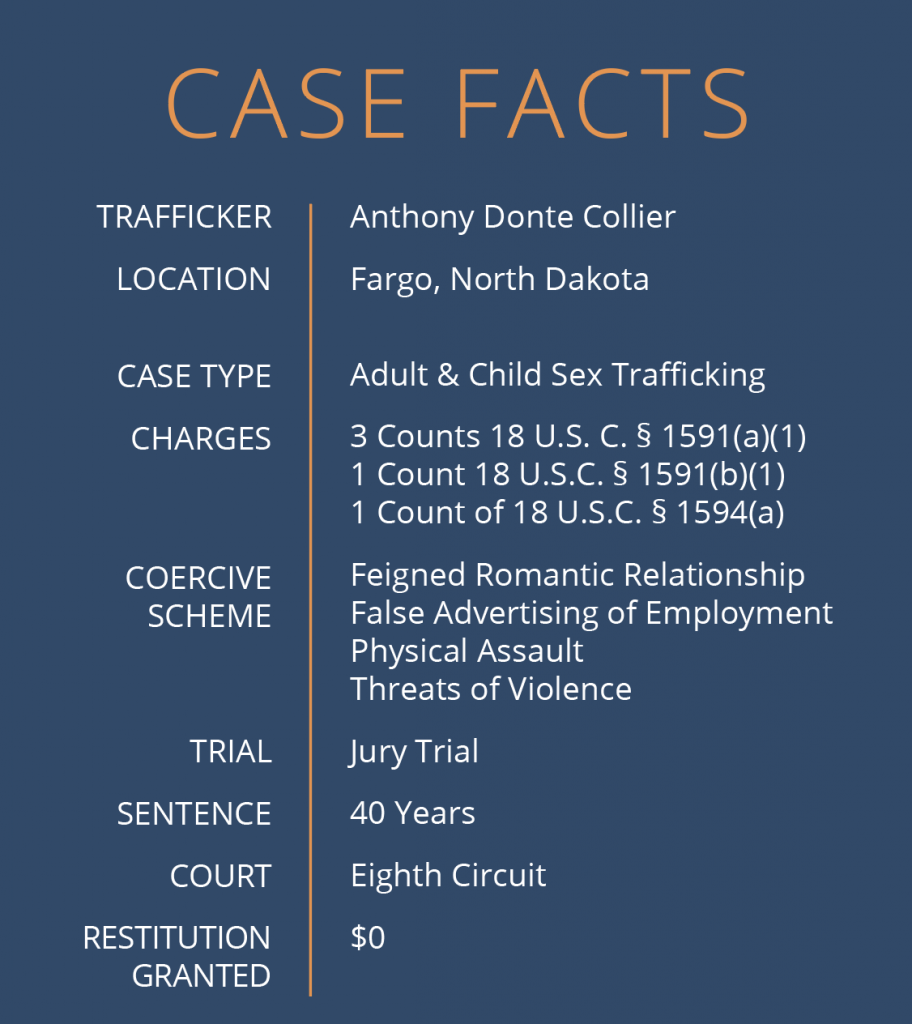

On November 5, 2017, authorities arrested Collier for violating conditions of his supervised release from a prior state crime. Prosecutors charged Collier with sex trafficking and attempted sex trafficking of four different women and one 17-year-old girl. Following a jury trial, the district court for the District of North Dakota convicted Collier of five counts of sex trafficking and attempted sex trafficking in violation of the Trafficking Victim’s Protection Act (TVPA) statutes 18 U.S.C. §§ 1591(a)(1), 1591(b)(1), and 1594(a). Collier appealed his convictions on several grounds, including:

- Whether the TVPA required that he knew his actions would affect interstate commerce

- The sufficiency of evidence regarding his use of force against his victims

- The admissibility of evidence regarding one victim’s background

- The sufficiency of evidence regarding his attempt to sexually traffic a minor

The Eighth Circuit rejected all four arguments and affirmed the district court’s decision.

Knowledge Not Required

First, Collier argued the TVPA required he “knew” his actions “affected interstate commerce” in his commission of the crime. Commonly in criminal cases, the prosecution must prove the defendant had a particular mens rea, or mental state when they committed a crime. This “knowledge” requirement centers on whether the defendant was consciously aware of the action being taken and its consequences. The mental state of the defendant at the time the crime was committed can impact which crime a defendant is charged with, as well as the severity of a punishment that a defendant is sentenced to. For example, if a person “knowingly” kills another person, they can be charged with murder; however, if a person “negligently” kills another person, they are usually charged with a lesser crime, such as manslaughter.

The TVPA requires the defendant’s criminal conduct to “affect interstate commerce” in order for the federal government to have jurisdiction over the crime. This merely means the defendant’s actions must have some impact on commerce in more than one state. This requirement can be satisfied by a defendant: driving victims across state borders, trafficking victims out of a hotel chain with a multi-state presence, advertising victims on a multi-state platform such as an internet website or social media platform, setting up dates with johns by cell phone, or even using condoms manufactured in another state. The bar is low. It does not require the defendant or the victims to cross state lines. Instead, the prosecution must prove the trafficking operation somehow utilized interstate commerce.

This merely means the defendant’s actions must have some impact on commerce in more than one state. This requirement can be satisfied by a defendant: driving victims across state borders, trafficking victims out of a hotel chain with a multi-state presence, advertising victims on a multi-state platform such as an internet website or social media platform, setting up dates with johns by cell phone, or even using condoms manufactured in another state. The bar is low. It does not require the defendant or the victims to cross state lines. Instead, the prosecution must prove the trafficking operation somehow utilized interstate commerce.

The Eighth Circuit rejected Collier’s argument that the TVPA required him to know his actions affected interstate commerce. Instead, the Circuit sided with the Second2, Fifth3, Seventh4, Ninth5, and Eleventh6 circuits which previously concluded “knowingly” does not apply to the interstate commerce element. The Eighth Circuit agreed the prosecution must only prove whether Collier’s actions actually affected interstate commerce, not if Collier knew they did.7

Collier’s Other Arguments Rejected

Second, Collier argued there was insufficient evidence to show he used physical force against the victim. The Eighth Circuit rejected this argument, highlighting evidence undermining Collier’s challenge, including:

- A purchaser’s testimony the victim showed up with a black eye;

- The victim’s own text messages to Collier asking him not to beat her up because she had more money for him;

- Jail calls from Collier ordering a victim to continue prostituting herself to help fund his jail account; and

- Jail calls Collier made to his brother telling him to use whatever force was necessary to keep the victim in check.

Third, Collier argued evidence of his victim’s prior voluntary engagement in commercial sex precluded the finding he forced her to engage in commercial sex. The Eighth Circuit stated, per Federal Rule of Evidence 412 and the Eighth Circuit’s own prior holding in United States v. Roy8, evidence of a victim’s participation in prostitution either before or after the time period in the indictment has no relevance to whether the defendant forced, coerced, or defrauded her into committing commercial sex.

Finally, Collier appealed his sex trafficking conviction regarding the minor victim because the minor never actually engaged in commercial sex. The Eighth Circuit relied on its prior holding in United States v. Paul, 885 F.3d 1099, 1101 (8th Cir. 2018). In that case, the Eighth Circuit joined seven other circuits in finding a § 1591 sex trafficking conviction does not require a completed commercial sex act.9 Though the 17-year-old victim testified she did not actually engage in commercial sex, there was sufficient evidence Collier recruited her, knowing she was under the age of 18, with the intent she engage in commercial sex. The Eighth Circuit held this was sufficient evidence to support his conviction.

Conclusion

The Eighth Circuit’s decision underscored three key principles about human trafficking prosecutions in federal court:

- A federal court has jurisdiction to preside over a human trafficking case if a trafficker’s actions affected interstate commerce, regardless of whether the trafficker had knowledge of the interstate nexus.

- A trafficker’s intention to sexually traffic a minor is sufficient to support a conviction, even if the minor never actually engaged in commercial sex.

- Similar to victims of rape and sexual assault, a trafficking victim’s sexual history, including a victim’s prior voluntary engagement in prostitution, has no place in the courtroom.

The Eighth Circuit joined the Second, Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits in finding that when a defendant, like Collier, (1) knowingly forced, coerced, and defrauded his victims into engaging in commercial sex and (2) that his actions affected interstate commerce, the defendant does not need to “know” that his actions affected it in order to be properly convicted of sex trafficking.

The Eighth Circuit’s rejections of Collier’s appellate affirmation of Collier’s conviction claims provides hope for future prosecutors and victims when bringing similar cases in the future. What remains to be seen is whether remaining circuits will choose to follow in this currently uncontested practice.

- 1 Backpage is a former classified advertising website that had become the largest marketplace for buying and selling sex by the time that federal law enforcement agencies seized it in April 2018.

- 2 United States v. Corley, 679 F. App’x 1, 6 (2d Cir. 2017) (unpublished).

- 3 United States v. Phea, 755 F.3d 255, 265 (5th Cir. 2014) (holding jury instruction not requiring knowledge of the interstate nexus element in § 1591(a)(1) was not plainly erroneous).

- 4 United States v. Sawyer, 733 F.3d 228, 230 (7th Cir. 2013) (“[T]his court and others have concluded time and again that the interstate and foreign commerce elements in many other criminal statutes have no mens rea requirements.”).

- 5 United States v. Chang Ru Meng Backman, 817 F.3d 662, 667 (9th Cir. 2016) (noting the interstate nexus element grammatically does not tie to “knowingly”).

- 6 United States v. Baston, 818 F.3d 651, 662 (11th Cir. 2016).

- 7 This holding aligns with the Eighth Circuit’s prior holding that a mental state requirement does not apply to the interstate commerce element in 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) (prohibiting felons from possessing firearms or ammunition). See United States v. Garcia-Hernandez, 803 F.3d 994, 997 (8th Cir. 2015).

- 8 781 F.3d 416, 420 (8th Cir. 2015)

- 9 See United States v. Mozie, 752 F.3d 1271, 1286 (11th Cir. 2014) (accepting evidence that defendant recruited victims “to engage in commercial sex acts,” even though those acts never materialized, as sufficient to support a section 1591 conviction); United States v. Willoughby, 742 F.3d 229, 241 (6th Cir. 2014) (concluding that section 1591 offense was complete when defendant left victim at client’s home knowing she would be caused to perform a sex act); United States v. Garcia-Gonzalez, 714 F.3d 306, 312 (5th Cir. 2013) (reading section 1591 to require completed sex act as essential element “erases the meaning of ‘will be’ from” the statute); United States v. Jungers, 702 F.3d 1066, 1074 (8th Cir. 2013) (conviction under section 1591 does not require “engaging in a sex act”); United States v. Todd, 627 F.3d 329, 334 (9th Cir. 2010) (explaining that section 1591’s knowledge element means that, in committing offense, defendant plans to force the victim to engage in a commercial sex transaction); United States v. Corley, 679 Fed. Appx. 1, 2017 WL 549021, at *3 (2d Cir. 2017) (rejecting contention that section 1591 requires government to prove victim actually performed commercial sex act); United States v. Maynes, 880 F.3d 110, 114 (4th Cir. 2018).