By: RACHEL GEISSLER

In March 2016, 28-year-old Jermayne “Turtle” Whyte and his 26-year-old girlfriend Jennifer Castro met 16-year-old A.E. at a strip club in Florida.1 A.E. recently ran away from her family in California.2 Castro promised to “put [A.E.] in a better situation” and provided her with food, clothes, and a place to sleep.3 Alone in a new place, she jumped at Castro’s invitation to move in with the couple. Not long after she moved in, however, Whyte and Castro began pressuring A.E. to engage in prostitution.4 They solicited clients for A.E. in Florida strip clubs and on Backpage.com, fabricating false identities for her along the way.5 For her work in strip clubs, they gave her a fake ID card of a 25-year-old woman named “Jessica Berry.”6 In online posts, they advertised her as 20-year-old “Alize,” 21-year-old “Cali Rosebud,” 20-year-old “Kyla,” and 21-year-old “Rosa.”7

During those months, Castro and Whyte groomed A.E. for her work as a prostitute and managed every aspect of her interactions with the men who paid to have sex with her.8 They taught A.E. how to treat clients, how to do her makeup, and how to avoid undercover police officers.9 Whyte pretended to be A.E. in text conversations, while coordinating meetings with men. He drove her to these engagements—sometimes staying in the room while she had sex with between four and six men per day—and pocketed the money for himself and Castro after each transaction.10 Whyte forced A.E. to have sex with him, regularly beat her with a loaf of frozen bread to hide bruises, and burned her with cigarettes to control her.11 Even when Whyte was put in jail on unrelated charges, he continued to direct A.E.’s prostitution from behind bars.12

During those months, Castro and Whyte groomed A.E. for her work as a prostitute and managed every aspect of her interactions with the men who paid to have sex with her.8 They taught A.E. how to treat clients, how to do her makeup, and how to avoid undercover police officers.9 Whyte pretended to be A.E. in text conversations, while coordinating meetings with men. He drove her to these engagements—sometimes staying in the room while she had sex with between four and six men per day—and pocketed the money for himself and Castro after each transaction.10 Whyte forced A.E. to have sex with him, regularly beat her with a loaf of frozen bread to hide bruises, and burned her with cigarettes to control her.11 Even when Whyte was put in jail on unrelated charges, he continued to direct A.E.’s prostitution from behind bars.12

Castro and Whyte Found Guilty of Sex Trafficking A.E.

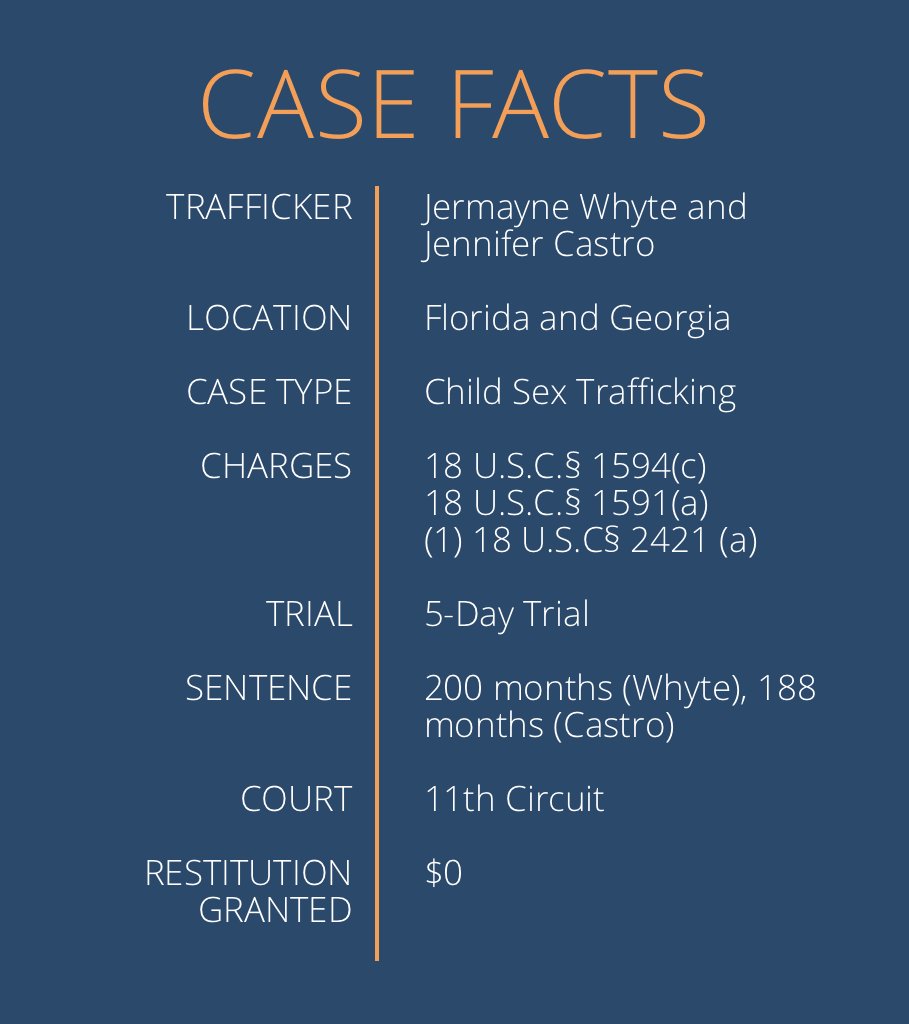

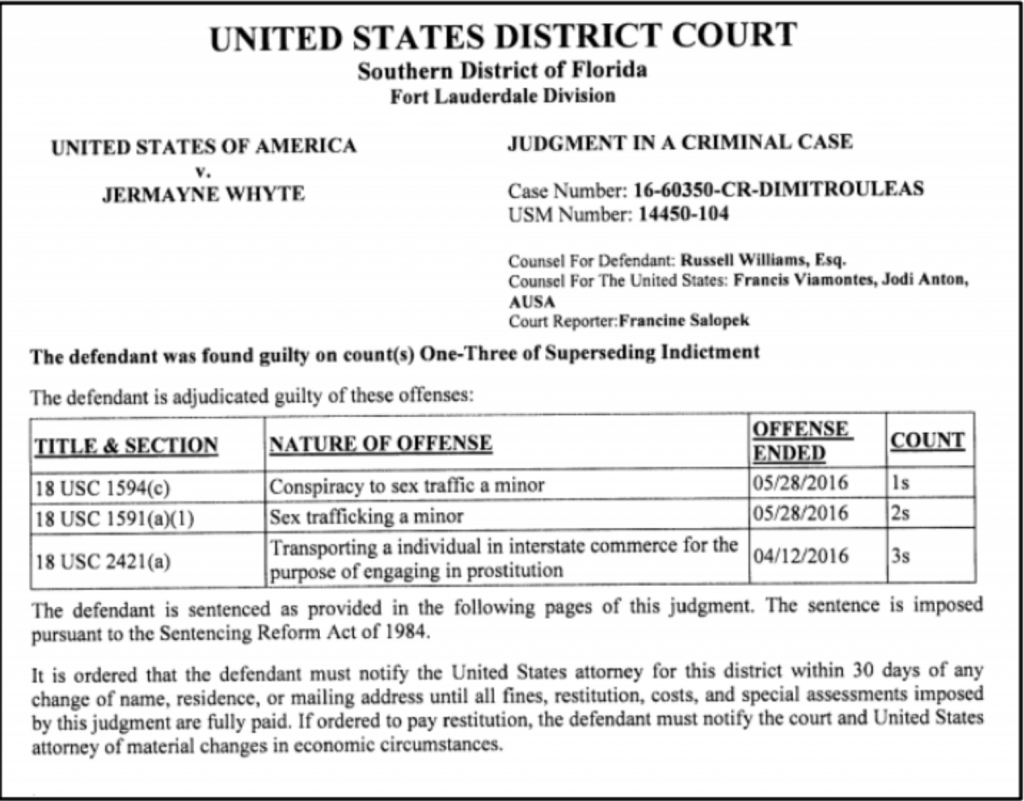

In response to a tip about a minor working as a prostitute in a Broward County, Florida strip club, FBI agents took custody of A.E. and used information she provided to search Whyte and Castro’s residence and arrest them both. Law enforcement agents corroborated A.E.’s story with text messages, cell site data, and Backpage.com ads posted by the “trick phone” Whyte used to communicate with A.E.’s clients. After a five-day jury trial, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida found both defendants guilty of conspiracy to sex traffic a minor pursuant to 18 U.S.C § 1594(c), sex trafficking of a minor under Section 1591(a)(1), and transporting an individual over state lines to engage in prostitution under Section 2421(a).13 The District Court sentenced Whyte to 200 months and Castro to 188 months in federal prison.14

Defendants Had a “Reasonable Opportunity to Observe” A.E.

Whyte and Castro appealed their judgments to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. They argued the district court erred in finding that the government sufficiently proved the knowledge element of the sex trafficking of a minor charge under Section 1591(a)(1), which requires the defendant to have knowingly caused a minor to “engage in a commercial sex act.”15 Although Section 1591(a) does require the defendant to have known or recklessly disregarded the victim’s age, a 2015 amendment to the statute added subsection (c), which plainly provides an exception: the government can prove the knowledge element by proving only that the defendant had a “reasonable opportunity to observe” the victim.16 Relying on case law that predated the 2015 amendment, defendants argued for use of the old standard, under which a mistake-of-age defense would have precluded their convictions.17 Defendants insisted they believed A.E. was an adult, a contention which contradicts statements Castro made to investigators about A.E. being “very immature” and suspecting A.E. “might [have been] lying about how old she was” from the time they met.18

Whether or not the defendants’ belief about A.E.’s age was genuine, the Eleventh Circuit flatly rejected their argument. The Court held that the amended statute “unambiguously creates an independent basis of liability when the government proves a defendant had a reasonable opportunity to observe the [minor] victim.”19 In doing so, the Eleventh Circuit joined the Second, Fifth, and Tenth Circuits’ interpretation of Section 1591(c).20

In addition to the “mistake of age” argument, the defendants argued that the “reasonable opportunity to observe” provision was unconstitutionally vague. This secondary argument also failed because, according to the Eleventh Circuit, the language of the statute is clear enough to give a person of ordinary intelligence “fair notice” of the type of conduct prohibited.21 In a prior case, the Eleventh Circuit held that “five or six interactions” between a trafficking victim and the perpetrator was enough to satisfy the observation requirement.22 The Defendants’ daily interactions with A.E. over the course of the two months in which she lived, ate, and slept with them provided ample opportunity for Whyte and Castro to observe her age.23

Other Issues on Appeal Related to the Defendants’ Knowledge of A.E.’s Age

Related to A.E.’s age, Castro argued the district court erred in giving the jury instructions on the conspiracy count that did not include knowledge of A.E.’s age as an element.24 A conviction based on jury instructions that misstate the law can be reversed, if the defendant can show that the mistake resulted in an unjust verdict, but there was no such mistake in Castro’s case.25 Pointing to longstanding Supreme Court precedent, the Eleventh Circuit clarified that the knowledge element from the substantive crime (sex trafficking of a minor) should be imported into the conspiracy charge, so “a reasonable opportunity to observe” is the knowledge element of both charges.26 Since the knowledge element was in the instruction for the substantive crime, the jury instruction for the conspiracy count did not need to include the knowledge element.

Finally, Whyte argued that the district court should have given him a sentence reduction for accepting responsibility for his crimes.27 The Eleventh Circuit rejected this argument because Whyte contested throughout the trial that he was not responsible for sex trafficking a minor because a reasonable observer would have believed A.E. was an adult.28 Thus, the Court reasoned, Whyte never accepted responsibility for his crimes and the district court appropriately declined the sentencing reduction.

What This Means Going Forward

The Eleventh Circuit’s opinion in United States v. Whyte confirms the interpretation of other circuit courts of appeals, making the government’s knowledge burden less strenuous under Section 1591(c) in the case of a sex trafficking of a minor. But as the Section 1591(c) provision gains more widespread usage by sex trafficking prosecutors, courts will need to further clarify what type, length, and frequency of interactions between perpetrator and victim constitute as a reasonable opportunity to observe.

-

- 1 Superseding Indictment at 1, United States v. Whyte, No. 16-CR-60350 (S.D. Fla. May 2, 2017). Inmate Search, Federal Bureau of Prisons, https://www.bop.gov/inmateloc/ (last visited Sept. 29, 2019).

- 2 United States v. Whyte, 928 F.3d 1317, 1323 (11th Cir. 2019).

- 3 Id.

- 4 Id.

- 5 Id.

- 6 Id.

- 7 Notice of Filing Defendant Jermayne Whyte’s Exhibit List and Exhibit, No. 16-CR-60350 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 1, 2017).

- 8 928 F.3d at 1323.

- 9 Id.

- 10 Id.

- 11 Paula McMahon, Feds: Sunrise Man Beat and Burned Runaway Teen, Forced her to Work as Stripper and Prostitute, South Florida Sun Sentinel (Dec. 28, 2016), https://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/broward/fl-runaway-trafficking-broward-palm-20161228-story.html.

- 12 928 F.3d at 1324.

- 13 Judgment at 1, United States v. Whyte, No. 16-CR-60350 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 20, 2017).

- 14 Id.

- 15 928 F.3d at 1328.

- 16 18 U.S.C. § 1591(a)(1) (2012); 18 U.S.C.A. § 1591(c) (West 2019).

- 17 928 F.3d at 1328.

- 18 Id. at 1324.

- 19 Id. at 1330.

- 20 See United States v. Robinson, 702 F.3d 22, 31–32 (2d Cir. 2012); United States v. Copeland, 820 F.3d 809, 813 (5th Cir. 2016); United States v. Duong, 848 F.3d 928, 931 (10th Cir. 2017).

- 21 928 F.3d at 1331.

- 22 United States v. Blake, 868 F.3d 960, 976 (11th Cir. 2017)

- 23 928 F.3d at 1331.

- 24 Id. at 1332.

- 25 Id.

- 26 Id. (citing United States v. Feola, 420 U.S. 671, 696 (1965)).

- 27 Id. at 1335.

- 28 Id.