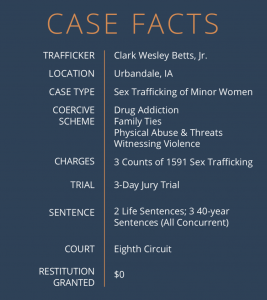

Over the course of one year, T.B. went from drinking alcohol with her friends to exchanging sex acts for crack cocaine, all because she had a family member with a strong addiction to crack cocaine and a plan to use his family members to get it.

In March 2015, Clark Wesley Betts, Jr., supplied a minor, T.B., and her friends with alcohol at a birthday party.1 In early 2016, when T.B. was 15-years-old, Betts offered her crack cocaine. He began smoking with her multiple times a week. Once T.B. was addicted, Betts manipulated her into having sexual intercourse with him while they were high. He then laid out the conditions that set his plan in motion: he would continue giving her crack cocaine only if she continued to have sexual intercourse with him.

In March 2015, Clark Wesley Betts, Jr., supplied a minor, T.B., and her friends with alcohol at a birthday party.1 In early 2016, when T.B. was 15-years-old, Betts offered her crack cocaine. He began smoking with her multiple times a week. Once T.B. was addicted, Betts manipulated her into having sexual intercourse with him while they were high. He then laid out the conditions that set his plan in motion: he would continue giving her crack cocaine only if she continued to have sexual intercourse with him.

Once Betts confirmed T.B.’s reliance on crack cocaine, his demands multiplied. He asked T.B. to see if her 12-year-old cousin, A.K., “would be interested in smoking crack cocaine with them.”2 He made sure A.K. was also addicted to the drug and then pressured both girls into having sexual intercourse with him in front of each other. He did so many times, using force or restraint when necessary. He was also physically violent in front of the girls. The two girls witnessed the conduct that led to Betts’ conviction for domestic assault.3

Betts had successfully used “drugs and alcohol as a ‘carrot’ and violence as a ‘stick’” to gain control.4

Betts tested his power over T.B. and A.K. on a new scale in the spring of 2016. He began bringing them to the house of his drug dealer, Vance Cooper, and, after a few visits, told them to perform sexual dances for Cooper and his friend. Cooper gave them crack cocaine in return. After this exchange, Betts directed both girls to exchange sexual acts for crack cocaine for themselves and Betts, even driving them to Cooper’s house himself.

Betts had achieved his goal—crack cocaine free of charge—but he did not stop there. He tried to recruit T.B.’s friend, whom he had previously given alcohol at the birthday party in 2015. Fortunately, he was stopped by her mother’s intervention and his arrest.

Guilty of Sex Trafficking and Drug Distribution

Police arrested Betts for a probation violation in March 2016. A few months later, after Cooper and his friend were arrested on federal drug charges, they told the government that Betts trafficked T.B. and A.K. in exchange for crack cocaine. This information sparked an investigation, and a grand jury indicted Betts in April 2017 for two counts of sex trafficking, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1591, and three counts of distribution of crack cocaine to a person under the age of 21.

On June 8, 2017, at the end of a three-day trial, the jury found Betts guilty of all five charges. District Judge Stephanie M. Rose sentenced Betts to life imprisonment for each sex trafficking charge and 40 years for each of the distribution charges.

Throughout the trial, the government sought to include evidence that supported its argument that Betts’ trafficking tied into “a larger pattern of grooming.”5 The government succeeded in introducing three pieces of evidence to that effect: (1) Betts’ supply of alcohol to T.B. and her friends at the birthday party in March 2015; (2) Betts’ prior sexual abuse of T.B. and A.K.; and (3) Betts’ physical violence in front of T.B. and A.K.6 These inclusions were the basis of Betts’ appeal, along with Sixth Amendment issues regarding Betts’ right to cross-examine A.K. about inconsistent statements and to introduce evidence about the victims’ sexual behavior after Betts’ arrest.7

Examining the Evidence: Grooming Process Is More Probative than Prejudicial

Betts’ main argument regarding Judge Rose’s evidentiary inclusions was that each of the three pieces of evidence was “extrinsic” to the case because it did not explicitly involve sex trafficking or distribution of crack cocaine.8 His defense distinguished alcohol from crack cocaine and his own exchange of sex for drugs from the experiences with the drug dealers. Therefore, he argued, the evidence was only allowed for limited uses, such as proving motive.

Betts further pointed out that even if the court decided the evidence was “intrinsic” because it showed “the context in which the charged crime occurred,”9 it was still subject to the question of whether it is more prejudicial than probative.10 He argued that the evidence should be excluded because the danger of unfair prejudice—due to the rape, violence, and criminal history—far outweighed the probative value of demonstrating the grooming process.

The Eighth Circuit affirmed the lower court’s holding, finding that all three evidentiary inclusions were intrinsic to the government’s theory of progressive grooming. The evidence in question explained why the girls used hard drugs and had sexual intercourse with Betts, and provided the necessary context for the jury to understand that Betts’ role was active rather than passive. While the district court had not explicitly addressed the prejudicial versus probative question, the Eighth Circuit held that the establishment of Betts’ control over the victims was probative enough to outweigh the prejudice that comes with evidence of rape of family members, violent behavior, and prior criminal history.

The Eighth Circuit’s decision in this case is significant because it expands other circuits’ decisions to admit evidence that shows a trafficker’s grooming process. In the past few years, various circuits have begun admitting evidence of victims’ past sexual abuse by defendants in sex trafficking cases. These courts have cited the same reasons as in this case: the evidence provides necessary context for the jury to understand the grooming process and is more probative than prejudicial.11 The Eighth Circuit’s ruling in Betts helps to solidify this precedent and extends this argument to two new kinds of evidence: (1) physical violence witnessed by victims12 and (2) the distribution of substances other than those in the criminal charge. Betts paves the way for more complete pictures of trafficking schemes in court, providing guidance to future courts on what constitutes a sex trafficker’s grooming process.

- 1 United States v. Betts, 911 F.3d 523, 527 (8th Cir. 2018).

- 2 Id. at 526.

- 3 Government’s Sentencing Memorandum at 13, United States v. Betts, No. 4:16-CR-00158 (S.D. Ia. 2018).

- 4 Betts, 911 F.3d at 530.

- 5 Id. at 527.

- 6 The district court required the government to link Betts’ past violence to the victims’ later acquiescent behavior in order to include it, and the government did so through expert testimony that victims who view their abusers’ violence are less likely to resist or disclose abuse.

- 7 For more information of the cross-examination and victim sexual behavior points, see the case in full. United States v. Betts, 911 F.3d 523 (2018).

- 8 Appellant’s Brief at 43-51, Betts, 911 F.3d 523 (2018) (No. 17-3592).

- 9 Betts, 911 F.3d at 529 (quoting United States v. Johnson, 463 F.3d 803, 808 (8th Cir. 2006).

- 10 “The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.” Fed. R. Evid. 403.

- 11 See, e.g., United States v. Steinmetz, 900 F.3d 595 (8th Cir. 2018); United States v. Thompson, 896 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2018); United States v. Gonyer, 761 F.3d 157 (1st Cir. 2014); United States v. Johnson, 132 F.3d 1279 (9th Cir. 1997).

- 12 Courts have admitted evidence of past physical violence to show the defendant’s intent and position, but these cases do not concern the effect of witnessing physical violence on the victim and do not discuss the grooming process. See, e.g., United States v. Geddes, 844 F.3d 983 (8th Cir. 2017) (allowing testimony from the defendant’s former girlfriend about him assaulting her and threatening to kill her to show his intent); United States v. Gemma, 818 F.3d 23 (1st Cir. 2016) (allowing evidence of physical violence of “prostitutes” other than victims to show the defendant’s role as a pimp).