By: CHRISTIN VIVONA

Nestled in the Rainbow Canyon of Caliente, Nevada, is the Caliente Youth Center – a juvenile detention center for at-risk youth in the Nevada area.1 The center exists to help struggling youth pave a new path for themselves. For two young men, Sha-Ron Haines and Tyral King2, that path did not materialize. Instead, the friendship they formed led to abuse, exploitation, and eventually, federal jail time.

After the two were released from the youth center, they remained close friends; Haines even lived with King’s family for a time.3 Then, in the spring of 2014, King introduced Haines to J.C., a 15-year-old friend of King’s girlfriend, A.S.4 The three were planning to make a trip from Nevada to California to make some cash by engaging the girls in prostitution.5 They asked Haines to join them, and he willingly agreed.6

After the two were released from the youth center, they remained close friends; Haines even lived with King’s family for a time.3 Then, in the spring of 2014, King introduced Haines to J.C., a 15-year-old friend of King’s girlfriend, A.S.4 The three were planning to make a trip from Nevada to California to make some cash by engaging the girls in prostitution.5 They asked Haines to join them, and he willingly agreed.6

Once in Pomona, California, Haines and King taught the girls how to negotiate prices with their “johns” and how to avoid undercover police. Once they were ready, J.C. and A.S. began walking the “track” to solicit “dates.” J.C. engaged in date after date in Pomona, each time calling Haines when she was done. She gave Haines all the money after each encounter.7

Next, the group traveled to Los Angeles, where J.C. and A.S. posted advertisements for prostitution on Backpage.com. King paid for the ads with his credit card, but Haines reimbursed him for J.C.’s costs.8 The posts were successful in soliciting buyers, so J.C. engaged in prostitution once again. In front of the grand jury, J.C. testified to giving her earnings over to Haines. She later recanted this testimony during the trial, claiming she kept the money she earned. 9

While the group was still in California, A.S. was arrested for prostitution. In an effort to raise her friend’s bail, J.C. had sex with one of A.S.’s customers. She received $1,000 for the “date.” This time, she kept the money. When Haines asked, she lied and told him she had not actually had sex with the customer. But Haines and King didn’t believe her. During the argument, J.C. told King to pull the car over. In the middle of the California desert, she got out of the car and began to walk. She found a ride to Walmart in Palmdale, California, where she prostituted herself to earn some cash. Then, she changed her mind and decided to meet up with Haines. Together, the two returned to Las Vegas.10

Arrest to “Protect the Powerless”

In 2014, the Project Safe Childhood Task Force of Nevada, a collaboration between federal and local law enforcement agencies, launched “Protect the Powerless,” an undercover operation focused on bringing “child pornographers, molesters, rapists, and sex traffickers to justice.”12 During the campaign, a Clark County probation officer reached out to Las Vegas Metropolitan Police with a tip. They had reason to believe a 15-year-old girl (later confirmed to be J.C.) was engaging in prostitution.13 Then, in September 2014, the Las Vegas Police Metro Police arrested the 15-year-old’s suspected trafficker — Sha-Ron Haines.

Building a Case

On July 17, 2014, J.C. was also arrested. After refusing to cooperate with officers in Haines’s case, she was charged with violating her parole. The officers then used J.C.’s phone number to find her prostitution ads on Backpage.com. Unable to hide the truth, J.C. admitted to a juvenile detention officer she had been working as a prostitute. She willingly gave over her phone, where the officer found text messages confirming her admission. Some of these messages mentioned Haines, either by name or by his nickname, “Lil’ Buzzy.”14

Haines later contacted J.C. from jail, where he instructed her not to testify at trial. He told her to stay off social media, so she could not be found. He said she was the key to the prosecution’s case, and if she did not testify, the government would have no case at all. J.C. willingly agreed not to testify at trial. Remaining loyal, she refused to help the government’s case.15

Trial and Conviction

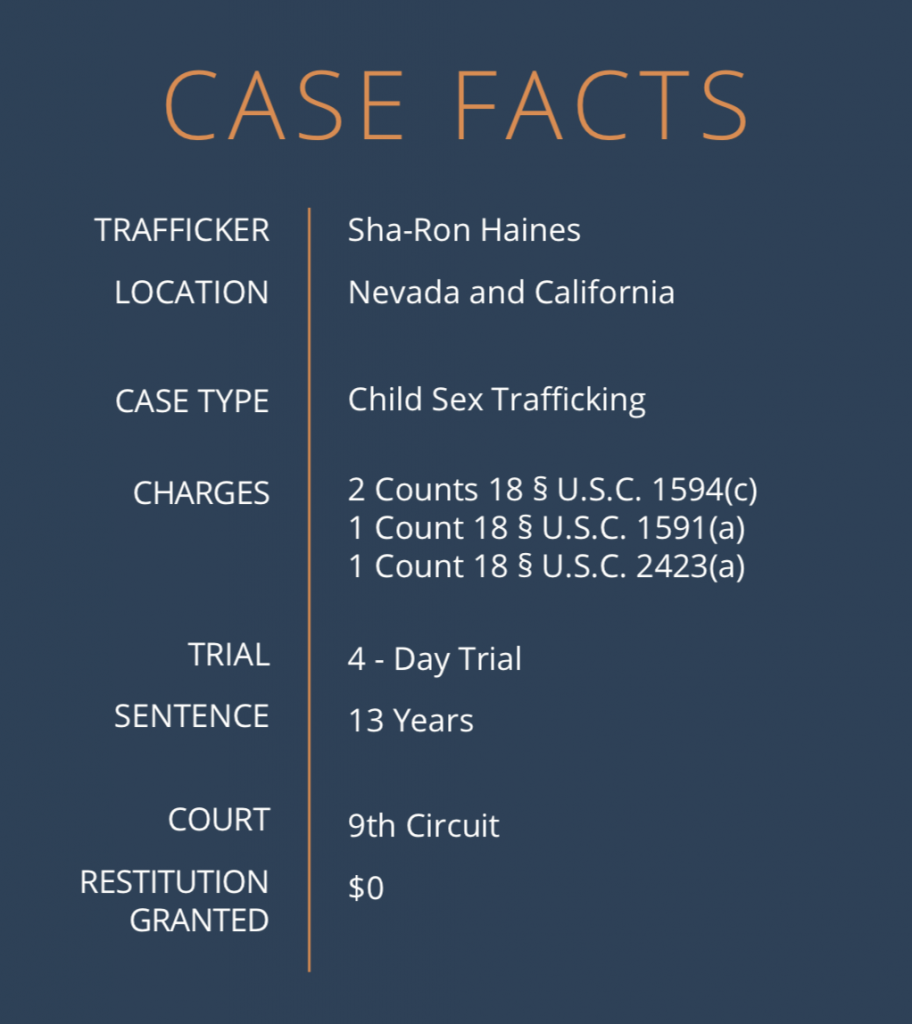

On August 6, 2014, a Grand Jury indicted Haines, charging him with transportation of a minor for prostitution and sex trafficking a child.16 On April 1, 2015, the jury returned a superseding indictment charging Haines with conspiracy to commit sex trafficking, sex trafficking, conspiracy to transport for prostitution or other illegal sexual activity, and transportation for prostitution or other illegal sexual activity.17

Haines’s trial began on August 17, 2015.18 Following the trial, the jury found Haines guilty on all four counts.19 Almost two years later, on January 30, 2017, Haines was sentenced to 156 months of imprisonment per count (all concurrent). Then, on February 10, 2017, he filed a notice of appeal.20

Evaluating the Evidence: Rule 412 and the Uncooperative Victim

On appeal, Haines argued the district court erred in excluding evidence of J.C.’s prior engagement in prostitution.21 During trial, the defense sought to question J.C. about her history of prostitution, during which time she did not have a pimp.22 Haines claimed this testimony would prove he did not coerce J.C. into prostitution. Instead, he argued he was just “along for the ride.”23

The district court excluded the testimony under Federal Rule of Evidence 412, which prohibits the use of the victim’s prior sexual history to prove “other sexual behavior” or “a victim’s sexual predisposition.”24 On appeal, Haines contended that J.C.’s testimony should not have been excluded under Rule 412, because it violated his constitutional right to present a complete defense and “his Sixth Amendment right to confront witnesses.”25 The Ninth Circuit rejected this argument, citing cases involving adult victims in which other circuits deemed the victim’s prior history to be irrelevant.26 According to these circuits, the fact that a victim agreed to commercial sex in the past does not mean she consented to force or coercion in the present case.27

Although the Ninth Circuit found these adult victims’ cases persuasive, it was particularly influenced by an Eighth Circuit decision, United States v. Elbert, which involved a minor victim, like Haines’s case. In Elbert, the Eighth Circuit rejected the defendant’s argument that evidence of a victim’s past prostitution proved the defendant did not cause victims to engage in commercial sex. The Court decided the government need not prove the elements of force, fraud, or coercion if the victim is a minor, because a minor cannot legally consent regardless of the absence of these elements.28 Since he failed to consider the implications of this Eighth Circuit decision, his argument was significantly weakened in the Ninth Circuit.

Although it is well established in the Ninth Circuit that Rule 412 prohibits the use of the victim’s sexual history in cases involving 18 U.S.C. § 1591, Haines’s case is slightly different than those heard in other courts. In this case, the victim (J.C.) was hostile to the government and did not want the rule’s protection. This was an issue of first impression in the Ninth Circuit, In fact, the Court did not find “a case discussing applicability of the Rule to a witness hostile to the government”29 in any other circuit court.

After United States v. Haines, the Court determined the victim’s willingness to testify and assist the government should not affect the applicability of Rule 412. In part, the rule is meant to keep prejudicial and inflammatory evidence away from the jury. Thus, a victim’s attitude toward this protection does not change its intended purpose.30

Conclusion

The Ninth Circuit was the first to decide the issue of the applicability of Rule 412 when the victim is hostile to the government and does not want protection. Its ruling seeks to maintain the even application of the rule so as to preserve its major purpose, to shield the jury from inflammatory evidence that is irrelevant to the case at hand.

- 1 “Caliente Youth Center (CYC).” Caliente. Accessed August 27, 2019. http://dcfs.nv.gov/Programs/JJS/Caliente/.

- 2 Opening Brief for Appellant – United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 1706139 at *9 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 3 Opening Brief for Appellant – United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 1706139 at *9 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 4 Answering Br. – United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *4 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 5 Opening Brief for Appellant – United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 1706139 at *2 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 6 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *4 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 7 Id.

- 8 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *5 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 9 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *6 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 10 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *6-7 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 11 United States v. Williams, 564 Fed.Appx. 568, 574 (2014)(“[evidence that defendant] provided his minor victims with drugs and engaged in sexual intercourse with at least two of them is inextricably linked with the charged misconduct of sex trafficking of a minor and/or attempted sex trafficking of a minor”).

- 12 Id.

- 13 Id.

- 14 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *7-8 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 15 Answering Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 3241112 at *8 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 16 Appellant Br. (United States v. Haines, No. 17-10059 2018 WL 1706139 at *3 (9th Cir. 2018).

- 17 Id.

- 18 Id.

- 19 Id. at *4.

- 20 Id. at *1.

- 21 United States v. Haines, 918 F.3d 694, 696 (9th Cir. 2019).

- 22 Id. at 696

- 23 Id.

- 24 Fed. R. Evid. 412 (*yr).

- 25 United States v. Haines, 918 F.3d 694, 697 (9th Cir. 2019).

- 26 Id.

- 27 Id. at 697-98 (quoting United States v. Rivera, 799 F.3d 180, 185-86 (2d Cir. 2015); United States v. Cephus, 684 F.3d 703, 708 (7th Cir. 2012).

- 28 Id. at 698. (quoting United States v. Elbert, 561 F.3d 771, 777 (8th Cir. 2009).

- 29 Id. at 699.

- 30 Id. at 699.