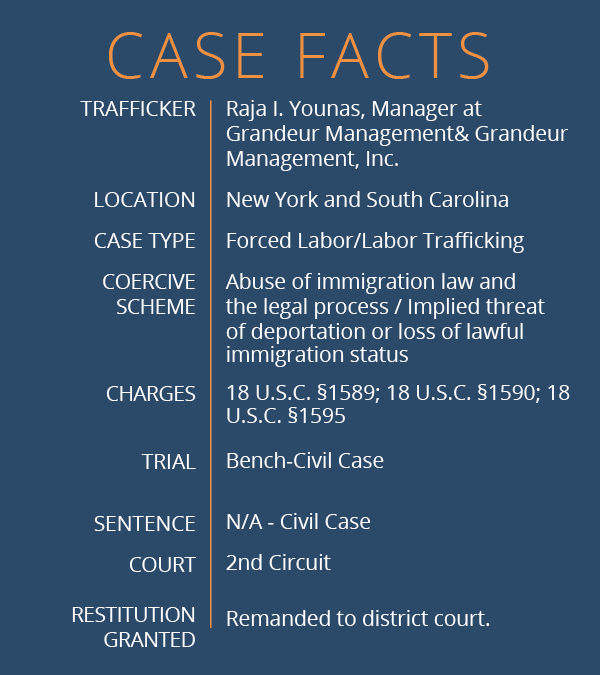

Recruited with the promise of better employment, Noel Adia moved from South Dakota to the sandy shores of South Carolina in October 2010. When he arrived, the promised job did not exist. Raja Younas, the man who recruited Adia, reassured him all would be well. If Adia remained patient and trustful, a job would arise.

As a foreign national from the Philippines, Adia was anxious. In order to be in compliance with his H-2B guest worker visa, he was required to be employed by a sponsoring company.1 While Adia waited without work, days turned to weeks, and weeks turned to months.

As a foreign national from the Philippines, Adia was anxious. In order to be in compliance with his H-2B guest worker visa, he was required to be employed by a sponsoring company.1 While Adia waited without work, days turned to weeks, and weeks turned to months.

Eventually, Younas told Adia he applied for an extension for Adia’s guest worker visa, and Younas’ employer, Grandeur Management (a hotel and resort services provider) would sponsor Adia. Younas sent Adia a copy of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) notice, acknowledging receipt of the extension petition on his behalf. Before Adia moved from South Dakota, Younas provided a copy of the USCIS transfer petition notice as evidence he transferred Adia’s visa sponsorship to Grandeur Management. Younas assured Adia the application would be sufficient for him to legally stay in the United States.

And yet, still, no job arose.

Don’t Ask Questions, Don’t Make Trouble

In late March 2011 — nearly six months after his first promise of employment — Younas instructed Adia to travel to New York for a prospective employment opportunity with a cleaning service. After the interview, Adia was hired as a housekeeping attendant at a hotel in Times Square. During this time, Grandeur Management paid Adia’s wages, and Younas monitored his employment service record.

In August 2011, Younas transferred Adia to another hotel in New York City where he worked as a doorman. Grandeur Management paid Adia $9 per hour for his services at the hotel. Although Adia regularly worked more than 40 hours per week, Grandeur Management never paid him overtime wages. Despite the long hours and low pay, Younas strongly advised Adia to rely on him. He made Adia promise not to look for other employment. Younas told Adia he would cancel or withdraw Adia’s guest worker sponsorship if Adia left Grandeur Management or “gave them any trouble” regarding work.2 Because the continuation of his immigration visa sponsorship depended on Grandeur Management, Adia understood the grave harm these veiled threats could bring him — possible deportation and an inability to return lawfully to the United States. Fearful of losing his lawful immigration visa status and remembering Younas’ threats, Adia kept his head down and continued to work.

By February 2012, almost a year after Adia began working in New York City, he finally summoned the courage to ask Younas for proof of his most recent seasonal guest worker visa sponsorship. Younas admitted to Adia he never actually filed the visa paperwork. As a result, Adia had been living and working in the United States for a significant period of time in violation of U.S. immigration laws.

After realizing he had been forced to work under false promises and misrepresentations, Adia stopped working for Grandeur Management.

Adia Asks the Courts for Justice Only to be First Denied

In 2017, Adia filed a civil complaint alleging that Younas’ actions constituted forced labor and human trafficking in violation of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA).3 Adia’s complaint alleged Grandeur Management and Younas conspired to fraudulently recruit him as a seasonal guest worker in New York City. Furthermore, they forced him to work overtime hours without proper compensation in fear of reprisal. Adia stated Younas pressured him to work using threats of loss of lawful immigration status, loss of employment, and false promises of visa sponsorships.

As relief, he requested unpaid overtime wages in addition to compensatory and punitive damages.4 Grandeur Management and Younas responded with a motion to dismiss Adia’s complaint based on a lack of stating sufficient facts to grant relief.5 The District Court for the Southern District of New York granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss the TVPA claims of forced labor and human trafficking against Grandeur Management and Younas.6 The district court did not find Younas’ alleged actions severe enough to constitute the “serious trafficking” Congress intended to outlaw when passing the TVPA.7 While dismissing the human trafficking claim, the district court held the defendants could not have transported Adia,8 because Adia was “already lawfully present in this country,” and “admits that he traveled [to New York] himself.”

Abuse of Immigration Process as Coercive Scheme

On appeal to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, Adia made one main argument: the facts he alleged were sufficient to claim a violation of both forced labor and human trafficking.

To violate the forced labor statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1589, a person must knowingly provide or obtain the labor or services of another by:

- “means of the abuse or threatened abuse of law or legal process” OR

- “means of any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause the person to believe that, if that person did not perform such labor or services, that person or another person would suffer serious harm or physical restraint.”9

Adia argued Younas, as an agent of Grandeur Management, threatened to alter or withdraw Adia’s immigration status — an abuse of the legal process — and caused Adia to believe he would suffer the serious harm of deportation if he did not continue to work for Grandeur Management.

The Second Circuit held, in the context of Adia’s circumstances, the alleged threat to cancel immigration sponsorship constituted abuse of the legal process; therefore, the evidence presented was sufficient to allege a claim of forced labor. Furthermore, in reliance on a U.S. Supreme Court case from the 1980s10 as well as a more recent Tenth Circuit case,11 the Second Circuit found that threats of deportation can constitute “serious harm” sufficient to compel an individual to continue to provide labor or services.12

Additionally, the Second Circuit held, based on Younas’ recruitment efforts to bring Adia from South Dakota to South Carolina, Adia pled sufficient facts to constitute surviving human trafficking under 18 U.S.C. § 1590.13 A person violates § 1590 when he or she “knowingly recruits, harbors, transports, provides or obtains by any means, any person for labor or services in violation” of the statutes prohibiting, inter alia,14 forced labor.15 As support for this claim for human trafficking, Adia argued Younas, as an agent of Grandeur Management, recruited him to work with the false promise of transferring and sponsoring his H-2B visa. He argued Younas then obtained his labor and forced him to work without overtime compensation. Applying the same logic and evidence from the claim of forced labor, the Second Circuit held the Southern District of New York improperly dismissed Adia’s human trafficking claim under § 1590.16

Overall, the Second Circuit held Adia “plausibly”17 alleged enough facts that his claims should not have been outright dismissed. The Second Circuit remanded the case back to the Southern District of New York for further proceedings to determine if the alleged facts and evidence presented amounted to violations of labor trafficking.

After the Second Circuit’s decision in Adia, those who employ foreign laborers should be on notice. Under the federal trafficking and forced labor statutes, no one is allowed to compel an individual to provide labor through threats of serious harm or other forms of coercion, force, or fraud. This includes threats of deportation. Employers who attempt to leverage legal immigration status to compel an individual to continue to work in underpaid and overworked conditions are not shielded from liability under the federal human trafficking statute.

Adia’s civil suit is currently pending in the U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York. There, the court will determine whether the facts of this particular case constituted forced labor and human trafficking.

A Quick Debunking of Trafficking Myths

In addition to providing notice of potential liability to employers of seasonal guest worker visas, the Second Circuit’s opinion debunks several common myths about human trafficking perpetuated by the District Court. The Second Circuit affirms the following important principles about human trafficking and federal anti-trafficking legislation:

- Human trafficking does not require cross-border – or any – transportation or movement.18 Instead, human trafficking centers on whether a defendant used force, fraud, or coercion to compel labor or commercial sex.

- The TVPA protects both foreign and domestic individuals from human trafficking. Though trafficking impacts all people groups, individuals who reside in the United States with conditional or no immigration status are particularly vulnerable to exploitation, as traffickers often rely on threats of deportation to force compliance. 19

- Workers who are paid a wage can still be trafficked. The legal inquiry is whether an individual voluntarily provided labor or whether an employer (or another party) used force, fraud, or coercion to obtain that labor unlawfully.

- Corporations are not immune from liability under the TVPA if they facilitate or financially profit from human trafficking.20

The Future of Coercion & Seasonal Guest Workers

Seasonal guest workers are often vulnerable to exploitation because their legal presence in the United States requires they maintain employment with their sponsoring agency. They cannot work for other employers and must leave the country when their job with that employer ends. Shackled to their employers, if seasonal guest workers complain about mistreatment or abuse, they face possible deportation or retaliation, in addition to the loss of necessary income to support their families.

This case raises important questions about where the line is drawn between wage theft or labor exploitation at the hands of an employer versus forced labor. Depending on how the district court rules on this case on remand, it could help delineate claims of wage theft or labor exploitation from those that rise to the level of labor trafficking. Foreign guest workers in the United States are some of the most vulnerable populations in our communities. This case serves as a reminder — it is ultimately the responsibility of employers to ensure they are providing fair and non-exploitative work and wages to all employees. Failing to do so could result in both corporate and managerial liability for forced labor and human trafficking.

- 1 See H-2B Temporary Non-Agricultural Workers, U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs. (last updated Aug. 18, 2019), https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/h-2b-temporary-non-agricultural-workers.

- 2 Adia v. Grandeur Mgmt, Inc., 933 F.3d 89, 91 (2d Cir. 2019).

- 3 Compl. ¶ 3.

- 4 Compl. at 14.

- 5 Def.’s Mot. Dismiss; Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6).

- 6 Adia v. Grandeur Mgmt., Inc., 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 153884, at *7 (S.D.N.Y Sep. 10, 2018).

- 7 Id.

- 8 Id. at *7.

- 9 18 U.S.C. § 1589.

- 10 United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988).

- 11 United States v. Kalu, 791 F.3d 1194 (10th Cir. 2015).

- 12 See United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931, 948 (1988); United States v. Kalu, 791 F.3d 1194, 1212 (10th Cir. 2015).

- 13 Adia, 933 F.3d at 94.

- 14 Latin for “among other things.”

- 15 18 U.S.C. § 1590.

- 16 Id. at 94.

- 17 Id. at 91.

- 18 Id.

- 19 Id.

- 20 Adia, 933 F.3d at 94 n. 3 (noting the district court’s error in applying case law interpreting a different statute, the Torture Victim Protection Act, which is also abbreviated TVPA).