By: FAITH LAKEN

In the summer of 2011, two Kazakhstani students traveled to Florida to work at a yoga studio, intending to participate in a cultural exchange program in Miami overseen by the U.S. Department of State. When they arrived, Jeffrey Cooper was waiting for them. Cooper did not, however, operate a yoga studio as he led them to believe. Instead, he owned an illicit prostitution and erotic massage enterprise.

A Fraudulent Job Offer Brings Students to the United States

To lure young, foreign women to the United States, Cooper posed as “Dr. Janardana Dasa,” claiming to operate “Janardana’s Yoga & Wellness” studio in Miami. Cooper fraudulently worked with a Kazakhstani travel agency to identify students interested in working at the studio as part of the U.S. State Department’s Summer Work Travel Program.1 Cooper developed a job description for the fake studio position, which included tasks such as “answering phones, doing clerical work, organizing retreats, and making appointments for massage, private yoga, et cetera.” After posting the job with the travel agency, he secured a program sponsor, as required by the State Department to qualify for the J-1 visa, based out of Chicago.2 In 2011, two Kazakhstani students received J-1 visas to work as receptionists at Cooper’s yoga studio. He promised to pay the students $12 per hour for their clerical work and provide housing above the studio for $70 per week.

Upon arrival, the students were shocked to learn there was no Dr. Dasa. The paid work Cooper promised at a yoga studio did not exist. Instead, Cooper advertised his “travel students” on Backpage.com with advertisements promoting their services, which included “erotic full body massages,” “exotic full body rubs,” and “tantric treatments” in Miami Beach.3 He ran the illicit business out of the Bayshore Yacht and Tennis Club, where clients came to the apartments he leased, expecting to pay for and receive sexual services.

The students tried to find alternative jobs and housing to no avail. Witnesses later testified the students felt helpless. They spoke little English, had never been to the United States before, and had no family in the country. Their legal status in the United States was tied to their employment for Cooper.

Police began investigating Cooper after neighbors reported they believed he was prostituting women from his apartment. A government sting operation in August 2011 identified the students. They returned to Kazakhstan later that summer while Cooper continued operating his business and the U.S. government mounted its case.

Criminal Proceedings

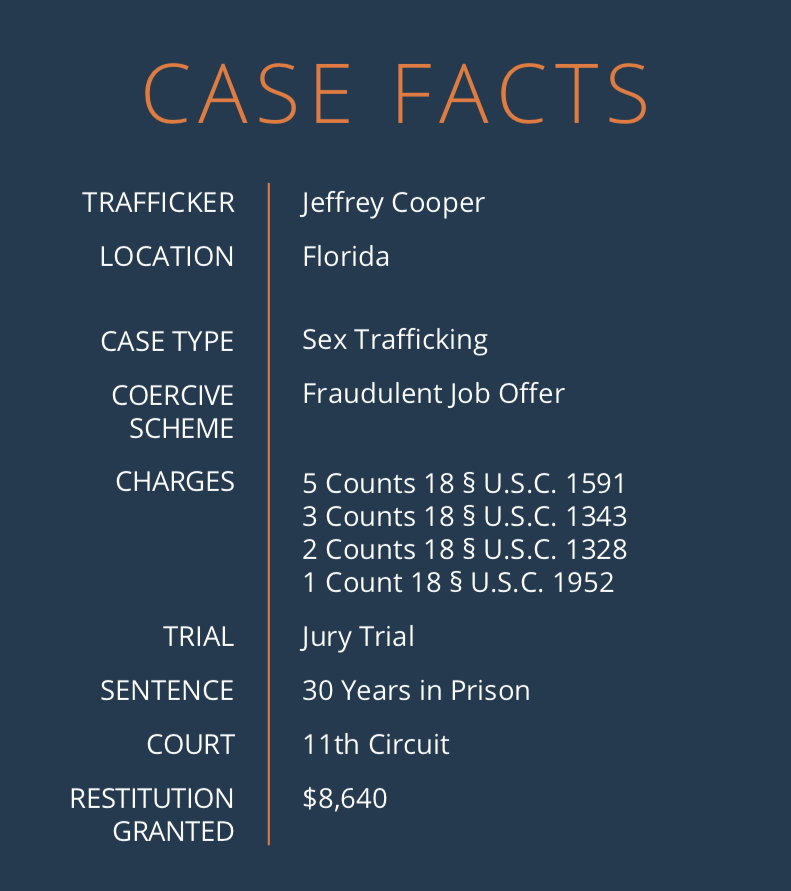

In 2016 — five years after law enforcement’s initial investigation — authorities arrested Cooper following a series of sting operations, undercover investigations, and interviews. Among other charges, federal prosecutors indicted Cooper for sex trafficking. In November 2016, a jury in the Southern District of Florida convicted him on five counts of sex trafficking and attempted sex trafficking by fraud, three counts of wire fraud, two counts of importing and attempting to import aliens for prostitution or immoral purposes, and one count of using a facility of interstate commerce to operate a prostitution enterprise. In March 2017, the presiding judge sentenced Cooper to 30 years in prison for his crimes. The judge also ordered restitution in the amount of $8,640.

On appeal, Cooper challenged the sufficiency of the evidence used to convict him, the admission of certain evidence, and the application of a sentencing enhancement, among other issues. The Eleventh Circuit ultimately affirmed the convictions and sentence.

Elbert P. Tuttle U.S. Court of Appeals Building in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo: Rebecca Breyer

Challenge to the Sufficiency of the Evidence

First, Cooper argued there was insufficient evidence to convict him of sex trafficking and attempted sex trafficking by fraud.

Because the students returned to their home country, the prosecution relied on other forms of evidence besides victim testimony. The Eleventh Circuit found that the documents Cooper submitted for the program sponsor’s approval, along with his messages to the travel agency employee, demonstrated that “he led the students to believe that they were hired to do clerical and office work.”4 The Eleventh Circuit also found Cooper’s comments during a monitored phone call with one of the students to support the finding that “he lied about having office jobs for the students at the yoga studio.” Furthermore, Facebook correspondence demonstrated the students “were surprised to learn that they were required to do sex work” and did not voluntarily provide the sexual services.5 Evidence presented at trial also showed the students tried to find other work and affordable housing, without success.

Therefore, the Eleventh Circuit determined there was “sufficient evidence for the jury to find Cooper guilty of the sex trafficking charges, beyond a reasonable doubt.”6

Challenge to the Admission of Evidence

Second, Cooper challenged the admission of evidence about his prior involvement in prostitution, as well as testimony from law enforcement about why certain witnesses, including the victims, did not testify.

Evidence Concerning Cooper’s Prior Involvement in Prostitution

Cooper argued evidence about his previous facilitation of prostitution was inadmissible. Rule 404(b) of the Federal Rules of Evidence prohibits admitting “evidence of a crime, wrong, or other act…to prove a person’s character in order to show that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character.”7 Essentially, this means evidence of prior “bad acts” is inadmissible if the prosecution uses it to argue the defendant likely committed the alleged offenses because the defendant has engaged in illegal activities in the past.

During the initial trial, the district court admitted the prosecution’s evidence of prior conversations along with a log of contact information and descriptions of women Cooper previously prostituted. On appeal, Cooper challenged the admission of these exhibits as prior “bad act” evidence, arguing it was used to show he had the propensity to facilitate prostitution.

The Eleventh Circuit maintained the evidence was relevant to other issues, rather than his character, including Cooper’s “intent to continue to operate his sex business, knowing the type of business it was.” The Eleventh Circuit also held the district court did not err in admitting the evidence because it was “probative of the continuing nature of Cooper’s business” – which the government had to prove – and “because the probative value substantially outweighed the risk of unfair prejudice.”8

Testimony Concerning the Victims

Cooper also challenged the admission of testimony from law enforcement concerning the victims. Long before trial, the students returned to Kazakhstan. Although one student cooperated with law enforcement’s investigation while still in the United States, neither they nor the travel agent wished to return to the United States to testify during the proceedings. Therefore, the district court allowed law enforcement to testify to the individuals’ mental states. The agent told the jury the victims chose not to testify because they did not want to be humiliated, embarrassed, or further stressed.

Cooper challenged the agent’s testimony as hearsay which, under evidentiary rules, generally prohibits one person’s testimony as to what another person said. The Eleventh Circuit rejected this argument saying even if the testimony included hearsay, it was Cooper’s counsel who asked the agent why the students did not testify thereby opening the door to the testimony on cross-examination.

Cooper also challenged the testimony’s admission as a violation of the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which affords the accused the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.”9 This provision guarantees the right of defendants to face witnesses whose testimony is used against them and for the defendant to dispute that testimony. However, the Eleventh Circuit noted because the agent did not offer “testimonial statements”10 from the individuals, the agent’s statements did not implicate the Confrontation Clause.11

Application of the “Vulnerable Victim” Sentencing Enhancement

Finally, Cooper appealed the district court’s application of a two-level sentencing enhancement based on Cooper’s exploitation of the victims’ vulnerabilities. Under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, a federal judge can increase a convicted defendant’s sentence if the victim was particularly vulnerable (based on their age, or certain conditions and susceptibilities) and the defendant specifically targeted the victim based on that perceived vulnerability.12

Cooper challenged the district court’s application of this enhancement; however, the Eleventh Circuit found no error. In affirming the district court’s findings, the Eleventh Circuit underscored the students had never been to the United States and had no family there. Further, the students were told by Cooper they could not work for anyone else because he was their visa sponsor. He also threatened if they did not work for him, they would have to find alternative housing. Additionally, his sentence (even with the enhancement) fell below the potential maximum sentence for this type of crime, which is life imprisonment. Therefore, the Eleventh Circuit found no basis to reverse.13

The Eleventh Circuit, and others, have upheld the vulnerable victim enhancement under similar circumstances, including cases where a foreign victim was estranged from their home community and had no local ties,14 as well as ones involving other types of isolation, vulnerable age, and/or drug addiction, among other factors.15

Conclusion

In upholding Cooper’s convictions and sentence, the Eleventh Circuit underscores the TVPA’s critical purpose of protecting individuals, specifically those most vulnerable, from exploitation. This case exposes the vulnerabilities that individuals present in the United States on temporary visas face (particularly when their legal status is tied to a single employer) and highlights the need for continued efforts to screen employers for legitimacy when issuing visas tied to employment sponsors. Furthermore, this case serves as an excellent example of creative prosecutorial strategies and provides hope for prosecutors charged with holding traffickers accountable when victims are unable or unwilling to testify.

- 1 This program provides foreign college and university students with an opportunity to live and work in the United States, on a J-1 visa, during their summer vacations to expose them to the people, culture, and way of life in the United States.

- 2 United States v. Cooper, 926 F.3d 718, 728 (11th Cir. 2019).

- 3 Id.

- 4 Id. at 736.

- 5 Id.

- 6 Id.

- 7 Fed. R. Evid. 404(b).

- 8 926 F.3d 718, 733-34.

- 9 U.S.C.S. Const. amend. VI.

- 10 Testimonial statements are those of the nature that would be offered by a witness to aid prosecution during trial. They might identify the defendant as the perpetrator, describe the circumstances of the crime, or establish how certain elements of the offense are met.

- 11 926 F.3d 718, 731.

- 12 Id. at 740.

- 13 Id.

- 14 See, e.g., United States v. Backman, 817 F.3d 662 (9th Cir. 2016) (affirming the application of the vulnerable victim enhancement where the victim lacked lawful immigration status, had no ties to family or friends, did not speak or understand English, lacked alternate employment opportunities due to her immigration status, and urgently needed money to care for her injured son); United States v. Monsalve, 342 Fed. Appx. 451 (11th Cir. 2009) (affirming the application of the vulnerable victim enhancement where the victims were undocumented immigrants, lacked identification papers, were unemployed, spoke no English, had no family in the United States, and had no other place to live other than what the defendant provided).

- 15 See, e.g., United States v. Royal, 442 Fed. Appx. 794 (4th Cir. 2011); United States v. Jimenez-Calderon, 183 Fed. Appx. 274 (3rd Cir. 2006); United States v. Lowe, 763 Fed. Appx. 878 (11th Cir. 2019).