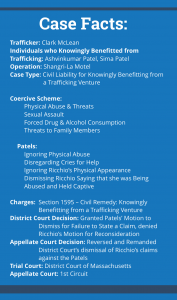

By: CORY SAGDUYU

Lisa Ricchio met Clark McLean through a friend in Maine in the winter of 2010-2011. Following their initial encounter, McLean made multiple requests for Ricchio to visit him in Massachusetts. Ricchio initially declined all of McLean’s offers. However, in June 2011, Ricchio eventually conceded to McLean’s appeals after he fabricated a cancer diagnosis and begged Ricchio to visit him in the hospital immediately. Once Ricchio arrived in Massachusetts, McLean told her he had discharged himself from the hospital and instead asked Ricchio to meet him at the Shangri-La Motel in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

After Ricchio entered the motel room, McLean changed drastically. He became extremely aggressive and abusive toward Ricchio, confiscating her cell phone, driver’s license, and car keys. Terrified, Ricchio begged him to let her go home. Instead, he forcibly raped her, leaving her visibly bruised.

Ricchio had fallen into McLean’s trap to groom her for prostitution. During the first night, Ricchio tried to escape from the motel. She made it outside of the motel room, where she encountered one of the motel owners, Ms. Patel. Crying, she told Ms. Patel that she was being abused and held captive by McLean. Ms. Patel physically brushed off Ricchio’s pleas for help, and kept walking. McLean then appeared, screamed at Ricchio, and grabbed her by the neck in full view of Ms. Patel. He kicked her and dragged her back into the room. Ms. Patel ignored Ricchio’s cries for help, even as she was forced back under McLean’s control.

Over the next several days, McLean raped Ricchio at least once a day. To wear down her defenses; he yelled at her, threw her to the floor, and even burned her vagina with a cigarette. McLean refused to allow Ricchio to eat, permitting her to drink only vodka and cranberry juice. He also forced her to take oxycodone pills. McLean told Ricchio that this was her new lifestyle, and that “they would make a lot of money from her.” Ricchio asked if he was talking about forcing her to have sex for money. McLean said she would have to do whatever the clients wanted. He threatened to harm Ricchio and her family if she attempted to escape.

The Patels encountered Ricchio several times during her captivity. Once, when in the motel’s parking lot, McLean shook hands with Mr. Patel and told him that he wanted to make some money with him by “getting this thing going” again. Mr. Patel agreed, and he and McLean exchanged “high-fives.” Another time, they saw Ms. Patel, who greeted McLean warmly and completely ignored Ricchio, who was visibly bruised. During another encounter, Ms. Patel knocked on McLean’s motel room door. When McLean opened the door, Ms. Patel could see Ricchio, who was visibly bruised, emaciated, and disoriented. Instead of offering to help, Ms. Patel simply demanded more money from McLean for the motel room.

The Patels encountered Ricchio several times during her captivity. Once, when in the motel’s parking lot, McLean shook hands with Mr. Patel and told him that he wanted to make some money with him by “getting this thing going” again. Mr. Patel agreed, and he and McLean exchanged “high-fives.” Another time, they saw Ms. Patel, who greeted McLean warmly and completely ignored Ricchio, who was visibly bruised. During another encounter, Ms. Patel knocked on McLean’s motel room door. When McLean opened the door, Ms. Patel could see Ricchio, who was visibly bruised, emaciated, and disoriented. Instead of offering to help, Ms. Patel simply demanded more money from McLean for the motel room.

After multiple days of abuse, Ricchio successfully escaped from McLean’s control. She returned to Maine, where she fell into a deep depression, requiring comprehensive treatment to cope with the extreme trauma she survived. Ricchio contacted the police to report McLean’s actions. McLean was arrested and convicted of four counts of indecent assault and battery in state court. He was sentenced to two years in a correctional facility.

Ricchio’s Civil Claims Against McLean & the Patels under TVPA’s Section 1595

In October of 2015, Ricchio filed a civil suit under 18 U.S.C. § 1595, the civil liability provision of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) . In addition to her allegations against McLean, Ricchio asserted claims against Shangri-La Motel and the Patels, alleging that the Patels knowingly benefitted from McLean’s trafficking enterprise by accepting payment for the motel room, which the Patels knew was being used to promote forced prostitution.

Initially, the District Court dismissed Ricchio’s civil claim against the Patels for failure to plead sufficient facts. The District Court judge stated that although the Patels may have turned a blind eye to McLean’s abuse, the complaint failed to show that the Patels participated “in a trafficking venture” with McLean.

Ricchio then appealed the District Court’s dismissal. On appeal, the First Circuit found that Ricchio’s complaint included sufficient factual allegations and reasonable inferences to support her claims that the Patels participated in and knowingly benefited from the trafficking venture. In reversing the decision of the District Court, the First Circuit relied on Ricchio’s factual allegations that the Patels had nonchalantly ignored Ricchio’s pleas for help, demanded additional payment for the motel room upon signs of McLean’s exploitation of Ricchio, and agreed to “get this thing going again” through the enthusiastic exchange of high-fives in the motel’s parking lot. The First Circuit stated that the District Court reached the wrong conclusion by focusing on the facts in isolation instead of reading the complaint as a whole.

On April 5, 2017, Justice Souter, sitting by designation for the First Circuit Court of Appeals, reversed and remanded the case back to the District Court for further proceedings. The parties are currently undergoing discovery proceedings. By allowing the civil claims to proceed against Shangri-La Motel and the Patels, the First Circuit sends a strong warning to defendants who “turn a blind eye” to exploitation, while simultaneously benefitting from the trafficking enterprise.

The Development of “Benefitting” Liability under the TVPA

Ricchio’s suit against Shangri-La Motel and the Patels is the first civil suit that has been filed against a hotel under the TVPA’s civil-remedy provision. When initially passed in 2000, the TVPA focused primarily on the criminal prosecution of human traffickers. The 2003 Reauthorization of the Act added a private right of action for victims of human trafficking to seek civil damages against their traffickers only. The 2008 Reauthorization further expanded civil liability to apply to individuals who “knowingly benefit” from what they knew or should have known was a trafficking enterprise.1 The expanded liability in the 2008 Reauthorization of the TVPA was designed specifically to hold entities and individuals, such as the Shangri-La Motel and the Patels, liable for civil damages. The civil liability extends beyond motels and hotels to other entities, such as massage parlors, restaurants, and even online platforms, that facilitate or financially benefit from a trafficking enterprise.

Before the 2003 and 2008 TVPA Reauthorizations, alternative civil options for trafficking victims included state relief, such as suing in tort or using the civil liability prong of state trafficking laws. However, state laws varied greatly, creating inconsistencies for when defendants could be held civilly liable. Further, not all states have human trafficking laws that allow victims to win civil damages. The TVPA, through its 2008 Reauthorization, now provides a national standard of civil liability for individuals who benefit secondarily from trafficking activities.

While the outcome of Ricchio’s civil claims against Shangri-La Motel and the Patels remains uncertain, the First Circuit’s decision sends a strong warning to entities who attempt to undermine civil liability for participation in a trafficking venture by pretending to “turn a blind eye” to exploitative conduct. Ricchio v. McLean presents the first in what will hopefully become a series of cases that hold hotels and other entities accountable for knowingly benefitting from trafficking activities.

- 1 18 U.S.C. § 1595 permits victims of trafficking to recover from whoever knowingly benefits, financially or by receiving anything of value from participation in a venture which that person knew or should have known has engaged in an act [of trafficking].